by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Oct 24, 2014

Employers have a responsibility to make sure the person they hire for a position is a right fit for the job. Background checks are one important part of this process, as they help to determine whether a particular industry or position is suitable for an applicant with a certain criminal history. However, it is vital that criminal records are used properly and not discriminatorily.[i] They should not be used as a screening tool to automatically dismiss all applicants with felony convictions. Rather, they should be used in a discerning manner, causing an employer to examine whether a person’s criminal history has any relation to the position sought. If there is a strong correlation, then there may be reasonable grounds to remove the applicant from consideration. If not, the applicant deserves the same chance as any person to demonstrate his or her qualifications for a job.

What does it mean to “ban the box”?

“Banning the box” refers to removing the question about a person’s criminal history from the initial job application and postponing the question to a later point in the hiring process. This policy increases the likelihood that a person with a criminal record will get hired by giving the applicant an opportunity to demonstrate his or her qualifications for a job without automatically being screened from the hiring process.

Postponing the question of an applicant’s criminal history to a later point in the hiring process allows applicants to explain their criminal record to an employer in person. This face-to-face interaction is essential to increasing an ex-offender’s chance of becoming employed. It provides an ex-offender the opportunity to be candid about his or her past and to explain how overcoming setbacks have fashioned him or her into a qualified candidate for the position. This conversation gives an employer the chance to listen to the ex-offender’s story, relate to him or her as a person, and get a better grasp of the person’s character and strengths. By giving ex-offenders the opportunity to represent themselves in the best light and to prove how qualified they are for a position, an employer may find his or her best candidate for the job.

Who is “banning the box”?

States, counties, and cities across the nation are establishing fair hiring polices for ex-offenders by “banning the box” on applications for public employment.

As of September 2014, thirty states have a local or state-level “ban the box” fair hiring policy for public employers. Among these states, thirteen have enacted statewide fair hiring laws, and six have also extended the fair chance policy to government contractors or private employers.[ii]

Nationwide, almost seventy cities and counties – including Atlanta and Fulton County – have taken steps to remove barriers to employment for qualified workers with records, and twenty of these cities and counties have extended “ban the box” policies to government contractors or private employers.[iii]

Why should Georgia “ban the box”?

Although the Governor spoke of “banning the box” earlier this year, he has not yet issued an executive order for state employers to do so. Taking this decisive step will be important for continuing the reforms his office has worked so hard to carry out this year to improve outcomes for returning citizens.

By following the precedent set by Atlanta and Fulton County and officially embracing “ban the box” policies for state employers, the state can help more people with criminal records get good jobs for which they qualify. This, in turn, will improve their chance of successfully reintegrating into society, decrease their chance of recidivating, enable them to benefit employers, and allow them to contribute to the economy of the state.

Embracing this policy at the state level will also encourage county, city, and even private employers across Georgia to follow suit.

For proof that “ban the box” policies help people with criminal records get good jobs and benefit employers, check out Durham, NC’s success story by clicking here.

This post was adapted from Georgia Center for Opportunity’s December 2013 report titled Increasing Employment Opportunities for Ex-Offenders.

Image credit: GT L&E Blog (featured image) and Accurate Background, Inc.

[i] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records in Employment Decisions Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” Office of Legal Counsel, April 25, 2012, accessed November 29, 2013, http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/arrest_conviction.cfm.

[ii] National Employment Law Project, Ban the Box: U.S. Cities, Counties, and States Adopt Fair Hiring Policies to Reduce Unfair Barriers to Employment of People with Criminal Records, September 2014, ii, 3, http://www.nelp.org/page/-/SCLP/Ban-the-Box.Current.pdf?nocdn=1.

[iii] Ibid., 1-2.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Sep 29, 2014

Every Georgian is affected by the criminal justice system in some way. Whether it is paying taxes to fund the more than a billion dollars spent on prisons each year or knowing a loved one who has spent time behind bars, the justice system is becoming an increasingly familiar issue in the lives of Georgians.

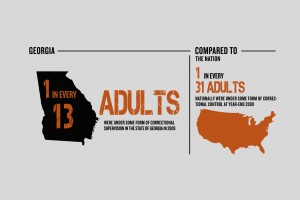

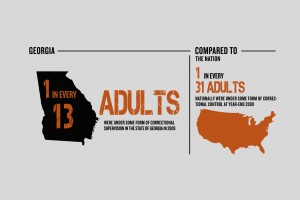

In 2009, the Pew Center on the States released a report revealing that 1 in 13 adults were under some form of correctional supervision in Georgia. This means that over half-a-million Georgians were either in jail, in prison, on parole, or on probation that year. This percentage far surpassed the national average, which was still an astonishing 1 in 31 adults under correctional supervision.

Even more staggering, 2.6 million people have a criminal record on file with the Georgia Crime Information Center, while the state’s total population is 10 million people. The collateral consequences associated with having a criminal record mean that as many as 1 in 4 Georgians likely face barriers to obtaining employment, housing, and even voting.

Currently, 53,000 people are incarcerated in Georgia, giving the state the fifth highest prison population in the nation. The incarcerated population more than doubled between 1990 and 2011, while the state’s general population increased by only half that rate during the same time period.

The Merry-Go-Round

Once a person enters the system, his or her likelihood of staying in it is fairly strong. The state releases 20,000 prisoners back into the community every year, and 2 out of 3 of those released are rearrested within three years. Nearly 1 in 3 are re-convicted within this time frame, resulting in re-incarceration.

While the state reports a recidivism rate of 30 percent over the past decade (determined by the number of offenders who are reconvicted within three years of release), the actual recidivism rate is closer to 50 percent – taking into account the number of people who commit a technical violation while on probation and parole, as well as the number of offenders who recidivate after the standard three-year time period.

The Cost

The effect of recidivism is very costly to the state: It negatively impacts public safety, results in burgeoning costs to taxpayers, and contributes to the breakdown of families.

Public Safety

Released offenders who continue to have unaddressed criminogenic (crime-producing) needs are likely to re-engage in criminal behavior and place themselves, their families, and their community at risk. Criminal behavior may arise from a substance abuse or mental health issue, from negative peer associations, from a poor family environment, from desperation caused by their inability to meet their basic needs for housing, employment, and transportation, and from a variety of other risk factors. Without addressing the underlying factors that lead returning citizens to engage in criminal behavior, the recidivism rate will continue to remain high as new crimes and technical violations of probation and parole are committed.

Taxpayers

Recidivism places a heavy burden on taxpayers. The cost to incarcerate one person for a year in Georgia is $21,000 – more than twice the amount the state spends toward educating one student for a year. This means that every cohort of released prisoners that recidivates amounts to $130 million annually, given the 30 percent recidivism rate and the 20,000 offenders released each year. Further, state expenditures on incarceration reached $1.1 billion in fiscal year 2010 – more than twice the amount spent in 1990, which was $492 million. For the amount taxpayers have spent on the prison system in recent years, the outcomes have been unacceptable.

Families

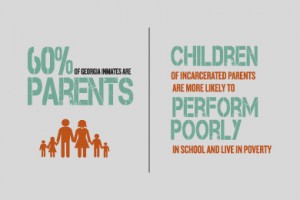

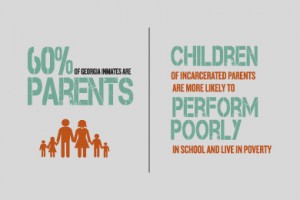

Finally, a person cycling in and out of prison creates instability in the life of his or her family. Significantly, 60 percent of inmates in Georgia are parents, and a number of these parents have been incarcerated more than once. Children of incarcerated parents are more likely to perform poorly in school, to be exposed to their parent’s substance abuse, to use drugs, to experience mental health issues, to experience domestic violence, and to live in poverty. Incarceration puts a tremendous strain on existing relationships, decreases the chances that partners will marry, transforms family roles, and often leads custodial parents to depend on public assistance. Families experience shame, anger, hurt, and despair at the incarceration of loved ones, creating inner turmoil that is often never addressed.

What Can Be Done?

Because of the enormous costs posed by incarceration and recidivism, it is essential for Georgia to promote solutions that will address underlying issues returning citizens face. This effort must take place at all points along the continuum, from the Governor’s Office down to individuals in the community.

Several areas of reform that Georgia Center for Opportunity’s Prisoner Reentry Working Group has addressed to improve reentry outcomes involve increasing employment opportunities (read report), restructuring debt, and developing the criminal justice and service provider workforce.

Employment

Employment plays a critical role in reducing offender recidivism, as it has the power to deter ex-offenders from crime and incentivize law-abiding behavior. Key barriers to employment that the working group identified include driver’s license suspensions, missing identification (i.e., Social Security cards and birth certificates), professional license restrictions, and employers’ negative perceptions.

To remove these barriers, the group recommended that the state lift suspensions on driver’s licenses for people who committed a non-driving related drug offense, offer incentives to employers to hire those with a criminal record, and have public and private employers postpone the question about an applicant’s criminal history to a later point in the interview process. Several of these recommendations were signed into law in April 2014.

Debt

Various state agencies enforcing the payment of debts and obligations without considering the needs and financial circumstance of returning citizens can lead them to recidivate. Returning citizens often carry excessive debt because of missed child support payments that accrue during their incarceration, court-imposed fees, fines, and surcharges for their offense, unpaid restitution, and the inability for them to earn money while in prison.

Several steps that the state can take to encourage returning citizens to repay this debt in a realistic manner include: Identifying offenders with child support orders upon entry to prison; providing offenders with pertinent information about their child support responsibilities; providing a grace period of 90 days upon release that gives returning citizens the opportunity to find a job and get back on their feet; and providing incentives for returning citizens to pay current obligations of child support and restitution by forgiving a portion of fines, fees, surcharges, and child support arrears owed to the state.

Workforce Development

There is an urgent need for the criminal justice workforce and community service providers to be trained in delivering evidence-based programs and practices. Without proper training and implementation, Georgia’s recidivism rate is likely to remain unchanged.

The state can better ensure successful reentry outcomes are reached by providing training and support to agencies and service professionals in the use of evidence-based practices, developing a hybrid degree program that combines criminal justice training and case management techniques, ensuring a risk/needs assessment is used and followed from entry into prison to treatment in the community, providing the workforce the ability to use graduated sanctions and incentives, and providing accountability to the workforce to ensure evidence-based practices are being used.

Conclusion

Each person involved with this reentry effort, from the governor to mentors in the community, need to put into practice what has shown to work in reducing recidivism. This effort will require education, training, resources, and coordination on all fronts, and it is one that should be pursued with fidelity. Doing so will help to bring restoration to families, build stronger communities, and ensure a more just society.

Click here to view The State of Corrections infographic

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Jun 25, 2014

Below is a guest blog by Jesse Wiese, Policy Analyst at Justice Fellowship, the legislative advocacy arm of Prison Fellowship Ministries.

Image Credit: Molly Rowan Leach/Feverpitched. All Rights Reserved. Found at Transformation.

For decades America has taken a “tough-on-crime” approach to criminal justice. This philosophy has generated little in the way of positive results and has resulted in burgeoning state budgets, overcrowded prisons, and low success rates. States are beginning to understand that we cannot incarcerate ourselves out of the problem of crime and recidivism. Fortunately, lawmakers are beginning to shift from a “tough-on-crime” approach and focus more on the science of criminology, or evidence-based-practices. This shift, however, is motivated predominantly by shrinking state budgets and the need to reduce the rising cost of corrections.

These reforms, while positive, do not go far enough. If we want to realize lasting change within the criminal justice system, we must do more than trim state budgets, institute new programs, or provide staff training — though these actions offer a good starting point. What is needed is a paradigm shift. We as a society need an altering of the lens through which we view crime, the men and women who commit it, and the victims and communities it affects. For a criminal justice system to be truly effective, it must recognize the broken moral foundations which lead to crime and provide a philosophical basis that perpetuates and restores the notions of human dignity and value.

Restorative justice addresses inefficiencies of the status quo and offers solutions that can provide lasting and refreshing change. By placing the victim at the center of the case, restorative justice places government in its rightful role as a facilitator of justice rather than a direct party. More importantly, restorative justice prioritizes victim participation, promotes offender responsibility, and cultivates community engagement. Identifying the needs and responsibilities of these three parties — victims, offenders, and community — is the fuel to realizing restorative outcomes and can be summed up in the following three questions:

First, do the victims and survivors of the criminal act have the right and opportunity to be validated and restored? Under the current system, the proper status of victims and survivors is usurped by the government’s unbalanced role of both victim and prosecutor. Restorative justice promotes the need for victims to be consistently considered throughout the criminal justice process. Although criminal acts often result in damages that can never be fully restored, victims and survivors have legal rights that should be enforced. Victims and survivors of crime may also need help regaining a sense of safety and control over their lives and assistance with damages they suffer, material or otherwise.

Second, are offenders given a fair process, proportionate and definitive punishment, and the expectation and opportunity to make amends? Restorative justice requires that the criminal justice system do more than warehouse people convicted of crimes. By holding men and women accountable for the harm they have caused to their victims and communities, the restorative justice process requires these men and women to take the necessary steps toward making amends and rebuilding trust within their communities. With the goal that those convicted of a crime are treated with dignity and fairness, restorative justice can ensure that punishments delivered will be proportional to the harm caused by the offense. Through this approach offenders are offered an opportunity for a fresh start, even if incarceration is necessary.

Third, is community safety improved and do communities play a role in restoring victims and those who have completed criminal punishment? Because crime affects communities by eroding public safety and confidence, disrupting order, and undermining common values, communities need to play an integral role in the restoration process. Additionally, communities can actively work to support victims and survivors of crime and help to facilitate the reintegration of those who have completed their criminal punishment. Government should, in turn, promote safety through proven crime reduction practices and the promotion of community education and solutions.

As a society, we have begun to consider the consequences of a “tough-on-crime” approach to criminal justice. Fortunately, there seems to be wide ranging support across both the political and religious spectrums for moving toward a system of restorative justice. However, the much-needed restorative justice reforms will only take place if citizens like you and me speak up, join together, and advocate for change.

You can do so by joining the Justice Fellowship Network. You will be kept up-to-date about reforms that advance restorative justice principles in your state and given opportunities to advocate for those reforms.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Jun 6, 2014

Prison is not typically the place where men openly share their feelings with each other, for fear of coming across as soft. However, several GCO team members experienced something markedly different while sitting-in on a fatherhood class at Clayton County Transitional Center.[i]

Reflecting on this experience, Breakthrough Fellow Michael Schulte writes:

It was wonderful to see the men open up as they spoke about their children, sharing their names, ages, and where they live now. One man had been away from his two kids for 14 years, and I could see by looking at his face how much it pained him. Many of these men are hopeful for the chance to simply be around their children again.

The fatherhood class is run by It Takes a Village Today (ITAVT), a non-profit whose name is derived from an ancient African proverb emphasizing community responsibility in the upbringing of children. As such, its mission is to preserve children and ensure they have a good upbringing through instilling the values of fatherhood within the men who will be returning to their families from prison.

The class provides a number of important services to the men including offering instruction on what it means to be a good father, helping noncustodial parents identify existing child support orders, and providing assistance in legitimizing children.

Concerning legitimation, Breakthrough Fellow Aundrea Gregg writes:

I was quite astounded by the number of men with unknown numbers of kids – men in need of help discovering once and for all who belongs to them. For fathers hopeful to build stronger relationships with their children, uncertainty of paternity can have serious implications…Any man wishing to gain rights to custody, visitation, or even have their children take their last name must complete the legitimation process…It Takes a Village…provide[s] the legal support that is needed for participants of the program to take paternity tests, file voluntary parental acknowledgement forms, and complete the legitimation process.

In addition to providing practical help, the class offers a forum for the men to speak openly about their children, share their goals as fathers, and reflect upon their own upbringing. Katherine Greene, Program Specialist with GCO, was particularly impacted as the men reflected on what sort of fathers they had while growing up. She explains:

One of the facilitators…asked two thought provoking questions: ‘What was your father like and how do you compare to him?’ Most of their responses surprised me. Many of them described their fathers as being positive role models in their lives. In the words of one inmate, ‘My father was a loving man. He was protective and very strict. He was present in my life. I just made some bad decisions which landed me in here.’ His words, among others who shared that day, really resonated with me.

Each of the GCO team members in attendance left the class feeling privileged to have learned about the men’s lives and were moved by the experience. Patrick Kaiser, Senior Manager of Research and Development, summed up the visit in the following words:

I think everyone should have a similar experience to see that these men are not like criminals portrayed in the media. Rather, they are men who have faced daunting challenges in their lives, made mistakes in how they tackled these challenges, and are looking to make amends for their errors and become positive community members. Many of these men were failed by their communities as children and young adults. We must not fail them again.

[i] Offenders entering transitional centers in Georgia typically have 6-12 months remaining in their sentence.

by Kimberly Sawatka | May 23, 2014

Below is a guest blog by Mrs. Sheila Caldwell, Director for Complete College Georgia at the University of North Georgia. Mrs. Caldwell currently serves as a member of GCO’s College & Career Pathways working group.

************************

In a recent poll of high school seniors asking how many credit hours per semester they should take when they go to college; more than 50 percent indicated 12 hours as an ideal college course load. Though 12 hours is a full-time course load, it is impossible for a student to earn a bachelor’s degree within four years unless a student takes an additional six hours during the summer. The primary route to earning a bachelor’s degree within four years is to successfully complete 15 credit hours per semester, for a total of 30 credit hours annually.

To improve college graduation rates and encourage on-time completion, the state of Georgia has launched 15 to Finish, a proven advisement, retention, progression, and graduation initiative that encourages students to take 15 credits per semester, thereby spending less time and money to earn a degree. The goal of Complete College Georgia and 15 to Finish is to provide better information and educate all students on tuition and fees, graduation rates, and job opportunities to ensure successful college completion.

The 15 to Finish initiative is important because many students express a desire to graduate within four years. Colleges are referred to as either four-year or two-year institutions, but most students are taking longer to graduate. In fact, if 100 students entered college today in the state of Georgia, only 11 students would graduate on time at a four-year college and only five would graduate on time at a two-year college (Complete College America, 2011). Full time-students are taking an average of five years to earn a bachelor’s degree and four years to earn an associate degree (Complete College Georgia, 2011). Many students are unaware of the potential consequences that can result from taking fewer credit hours, including a higher likelihood of non-completion, lost wages, and increased college costs.

A cost analysis conducted by the University System of Georgia seeking to determine how much a student would pay for a degree based on the number of credit hours taken per semester revealed staggering results. For example, a student enrolled in a bachelor’s degree program at the University of North Georgia (UNG) would pay an average of $42,236 to earn a degree by completing only three credit hours per semester compared to $26,768 if completing 15 hours per semester– nearly $15,000 in savings for a UNG student who graduates on time. The study found the cost difference is even more drastic for students who wish to attend Georgia Tech or the University of Georgia (UGA). The chart below illustrates an additional expense of $74,000 for Georgia Tech and $90,000 for UGA for students taking only 3 hours per semester.

|

Credits/

Semester

|

GA Tech

|

UGA

|

|

3

|

$119,474.00

|

$134,357.00

|

|

6

|

$75,914.00

|

$73,317.00

|

|

9

|

$72,875.00

|

$70,205.00

|

|

12

|

$56,164.00

|

$54,587.00

|

|

15

|

$45,514.00

|

$44,325.00

|

Not only do students reap significant financial benefits when they enroll in 15 hours every semester until degree completion, they also experience quicker entry and higher wages when they transition into the workforce. Students graduating from UNG with a bachelor’s degree earn an average of $20,000 more annually than their high school counterparts. A college student who graduates within four years with a bachelor’s degree earns $40,000 more in income than a college student who takes six years to graduate. Additionally, associate degree holders who graduate within 2 years earns $19,000 more than associate degree holders who take four years to graduate (Education Pays, 2013). Many part-time students do not consider the enormous amount of money foregone in the workforce when they delay college completion by one or two years.

Part-time students pay more for their degree and incur lost wages because they lack a college credential. They also jeopardize their entire college career. According to “Time is the Enemy” (CCA, 2011), only 15% of part-time students will earn a bachelor’s degree within six years compared to 57% of full-time students. Only 7.8% of associate degree seekers will earn a degree within four years. The 15 to Finish initiative seeks to battle dismal college completion rates.

College completion not only enhances an individual’s economic well-being, it can improve overall quality of life in the following ways: longer life spans, better access to health care, more prestigious employment and greater job satisfaction, less dependency on government assistance, greater participation in leisure, civic, and artistic activities, and more self- confidence (Education Pays, 2013).

Serving as a member of the College and Career Pathways working group, the Complete College Georgia (CCG) 15 to Finish initiative is perfectly aligned with recent discussions among the panel. The primary goals of the working group are to develop and promote programs that encourage at-risk youth to graduate high school and attain college and career success. GCO and CCG collaborate to help all students better prepare, connect to, and navigate college. Our ultimate aim is to enable greater mobility and opportunity among Georgia citizens.

*********************

Sheila Caldwell aims to help students successfully access and complete college at University of North Georgia. She is passionate about opportunity over charity and strives diligently to be a change agent for economically disadvantaged students across the state of Georgia.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Apr 18, 2014

Crime needs to be punished. There is no doubt about that. Punishment for crime is a necessary part of maintaining a just society, preserving order and peace, and promoting life and happiness. Citizens need to know that there are consequences for breaking the law and to be motivated to do what is right for the good of society.

While punishment for crime is necessary, it also needs to be dispensed justly. Overly punitive measures can demoralize offenders and their families and cause them to lose faith in the criminal justice system.

Take mandatory minimum sentencing for drug offenses, for instance. This sentencing began in the 1980’s as a way for state officials to get “tough on crime.” However, it stripped judges of the ability to use discretion in sentencing drug offenders, resulting in scores of people spending far too many years behind bars for relatively minor drug offenses. This “tough on crime” mentality led to a massive overcrowding of our nation’s prisons, more costs to taxpayers, and increased recidivism.

When thinking about punishing offenders for their crimes, we must remember that 95 percent of those who enter prison will return to the community at some point. In other words, “today’s prisoners are tomorrow’s neighbors.”[i]

This reality should cause us to approach how we administer justice with a more balanced and humane perspective. We ought to be thinking with the end in mind: How best can we prepare a person for reentry at the moment of sentencing? What obstacles does a person need to overcome personally? Who does this person need to make amends with before he is released? What will keep this person from recidivating?

It is important that we remember that those who have committed crimes are people, and all people have inherent dignity and worth. If we allow ourselves to view a person as less than human, we are tempted to write him off and to refuse to engage in the hard work of helping him to overcome root issues that keep him from thriving. However, if we see those who commit offenses as humans worthy of the same dignity as any other human being, we will be more likely to see their possibility for redemption.

When we examine our own lives – our failings and the consequences of bad choices that we’ve made – we can learn to relate to offenders and have compassion on them. It should show us that just as we have been shown mercy at various points in our lives and given the chance to move forward, criminal offenders likewise could benefit from being shown mercy. This does not mean that we should forgo punishing justly according to the nature of one’s offense, but it should temper the manner in which we approach punishing crime and cause us to reexamine the ultimate outcomes we are trying to achieve. This paradigm shift should cause us to realize that the offender’s restoration to one’s victims, family, and community, is a better aim for our criminal justice system than merely punishment.

A better approach seems to be one that recognizes that crimes are fundamentally committed against other people, not simply the state. The harm one person inflicts upon another needs to be addressed and repaired as best as possible. Simply locking a person away and having the state deal with him is not going to address the needs of the victim, the offender, or the community. A deeper reconciliation is needed.

A criminal justice system that reflects this restorative approach would be far more likely to cultivate a humane and just society.