Decarceration’s Disconnect: Corrections spending rises in Georgia even as prison population declines

Decarceration’s Disconnect: Corrections spending rises in Georgia even as prison population declines

Key Points

- The nation’s prison population has declined in many states, including in Georgia, but a new report shows that prison reforms to decrease the number of inmates haven’t translated into meaningful taxpayer savings.

- Departments of Corrections budgets are actually increasing throughout the country, but prison costs still account for no more than about 5% of most states’ total budgets.

- Instead of focusing on state prison budgets and costs per inmate, policymakers need to consider the total cost of crime—both monetary and social—that a community pays and how to reduce it.

Prison reform debates often focus on reducing prison populations to save taxpayers money. But is that actually possible?

In a new report for the Manhattan Institute, Joshua Crawford, a Public Safety Fellow at the Georgia Center for Opportunity (GCO), argues that marginally decreasing prison populations doesn’t yield the taxpayer savings policymakers have long touted. Crawford also shows that continuing to focus mainly on cost savings instead of on other measures to reduce crime and recidivism may lead to unintended fiscal and social consequences for states, including Georgia.

To understand this argument, it’s essential to first understand the landscape of state prison populations and the associated costs of incarcerating an individual.

Understanding prison populations and associated costs

State prison populations decreased by 24% overall between 2010 and 2023, with 43 out of 50 states experiencing a decline. But despite those significant decreases, Departments of Corrections budgets haven’t followed suit.

In fact, Crawford’s report shows there is little to no relationship between changes in prison populations and changes in corrections spending.

Departments of Corrections budgets are actually increasing, but corrections costs still account for no more than about 5% of most states’ total budgets.

Nevertheless, many policymakers and advocates continue to argue that cutting prison populations will save money. So where is the disconnect between the numbers and the messaging?

Most often, the total cost per inmate per year is calculated by dividing the total costs of the prison system by the number of incarcerated people, but this is a misleading figure. Many of the more costly parts of a Department of Corrections budget (e.g., staff salaries, utility bills) are long-run or fixed costs that don’t vary with marginal changes in a prison’s population. To get a more accurate estimate of possible savings, it’s more important to consider short-run costs, like food and toiletries, which can vary immediately with a change in a prison’s population.

Interpreting the numbers for Georgia prisons

Georgia is one of the 43 states that, on average, saw a decrease in their prison populations between 2010 and 2023. The state experienced an 11.7% decrease in the number of inmates during that time.

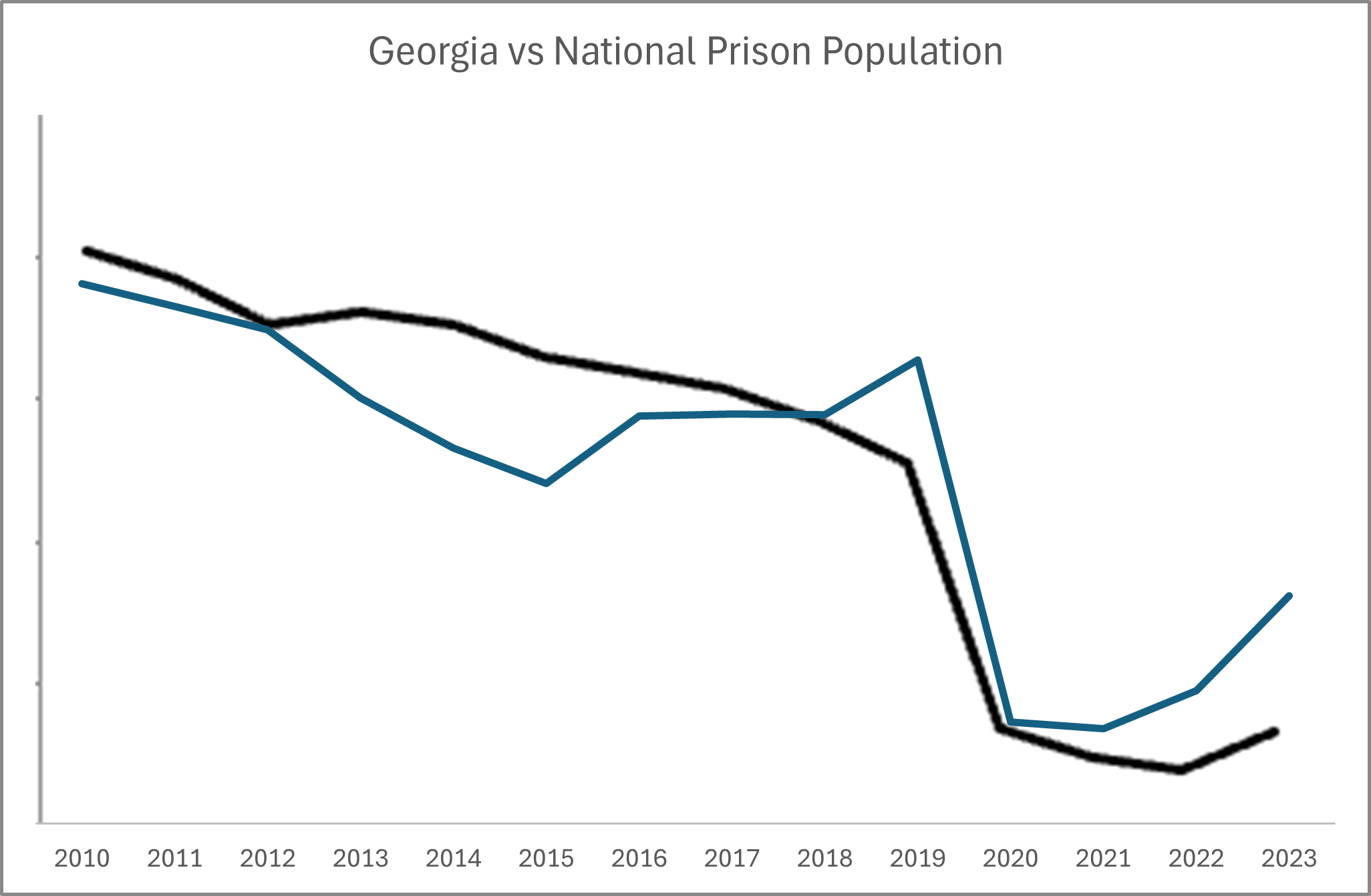

Georgia falls in line with overall national trends year over year. The figure below illustrates the decrease in both Georgia’s and the nation’s number of incarcerated people. The biggest departure was in 2019, when Georgia seemingly had a sharp increase, but that increase was actually minimal at just 2.2%.

And like most states in recent years, Georgia saw a rebound in the number of inmates after the COVID-19 pandemic, when more people were released to help alleviate stress on prison systems.

Black Line = National Trend, Blue Line = Georgia Trend

The data for Georgia also reinforces the lack of a relationship between the change in the number of inmates and the change in corrections spending. The table below reveals that even though Georgia’s prison population decreased from 2010 to 2023, corrections spending increased 23.6% during that time.

Data from 2019 further reinforces this absence of a relationship. During that year, Georgia saw a very slight increase of 1,169 people in its prison population, but the state spent $21,430 less on corrections that year compared to 2018.

A better focus for Georgia policymakers

Instead of focusing on state prison budgets and costs per inmate, policymakers need to consider the total cost of crime—both monetary and social—that a community pays and how to reduce it.

Crime itself costs our nation anywhere from $2.6 trillion to $5.76 trillion each year, with violent crime accounting for 85% of those costs. A single homicide can cost upwards of $9 million in government resources and lost potential earnings of victims. This doesn’t account for the financial burdens it can put on families and communities.

In addition to the monetary cost of crime, communities pay a significant social price—and none more so than high-crime, impoverished areas. Effective public safety measures are foundational to upward mobility. Without them, these communities will continue to see the loss of businesses, local resources, and community connections that help people flourish.

With this in mind, policymakers and advocates should refocus criminal justice efforts toward reforms proven to reduce crime and recidivism. Improvements on both of these fronts generate cost savings of their own, in addition to saving lives and lowering fear of personal harm.

Best practice criminal justice reforms fall into eight solution categories that could spark meaningful change:

- Addressing community disrepair

- Investing in a well-trained police force

- Building trust by protecting victims

- Addressing gang violence

- Addressing the low number of homicide detectives and low clearance rates

- Ensuring appropriate sentencing

- Implementing cognitive behavioral therapy for juvenile offenders

- Evaluating and updating re-entry programs

In Georgia, policymakers and advocates should consider these specific efforts to reduce crime and recidivism:

- Implementing reforms to help law enforcement close non-fatal shooting cases (e.g., the Firearm Assault Shoot Team in Denver, Colorado)

- Broadening cognitive behavioral therapy offerings for juvenile offenders, which has shown promising results in juvenile recidivism rates

- Prioritizing data collection and evaluation to help guide future programs and reforms

- Helping communities through a holistic approach that includes job training and opportunities, affordable housing, and family programs

In addition to the above policy suggestions, GCO has prepared in-depth reports focusing on reducing crime in two major Georgia cities—Atlanta and Columbus.

As Crawford says of potential criminal justice reforms in Georgia, “lawmakers should focus conversations about criminal justice where they belong: on protecting the public and creating a fair and just system that values the lives, liberty, and property of Georgia families.” In doing so, policymakers can transform entire communities by making them safer for the people who live there.

Image Credit: Canva