The Best Administrative Structure for Welfare

The Best Administrative Structure for Welfare

By Erik Randolph

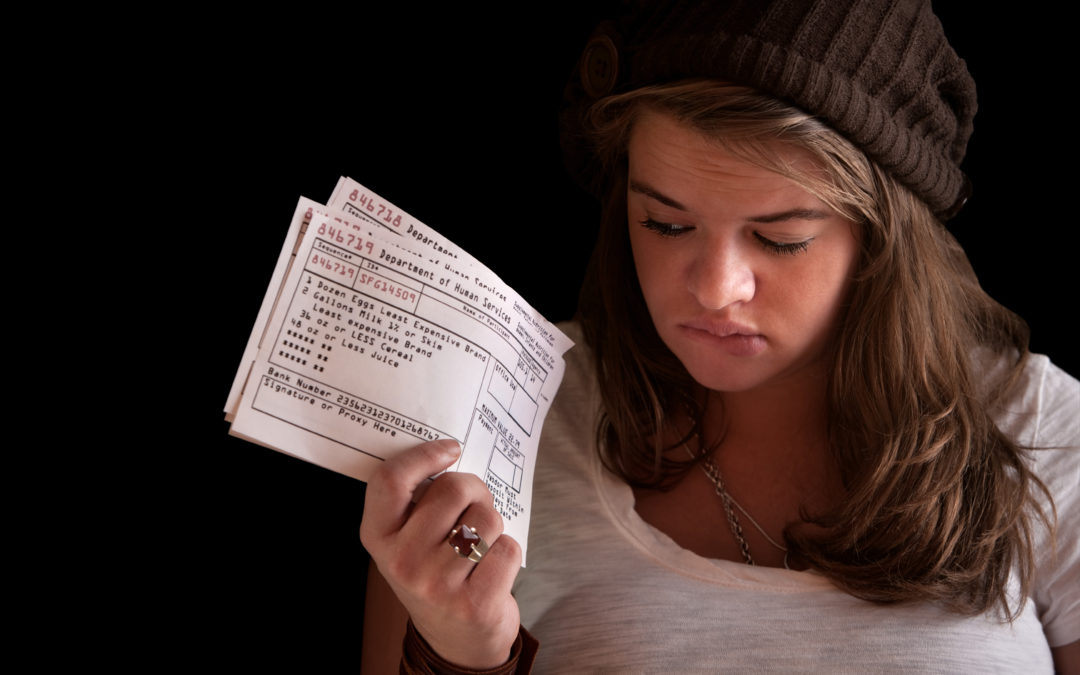

When someone needs financial help or workforce training from the government, where do they go?

If we just allowed people to navigate federal programs on their own, the average person would be completely overwhelmed.

Fortunately, states have some control over the process for some of the larger programs, like food stamps and Medicaid, that serve millions of Americans.

Georgia’s Gateway Strategy

Compared to many states, Georgia is ahead. The state government has spent years and $262 million to streamline its eligibility systems of means-tested programs into an integrated system known as the Georgia Gateway.

Here there is just one “door” to enter to qualify for some of the big federal means-tested programs entrusted to the states to administer.

The awarding-winning Gateway allows individuals to apply for ten programs across four state agencies, including food stamps; food packages from the Women, Infants, and Children Program; Medicaid; subsidized childcare; and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

The Department of Human Services runs the eligibility system at an annual operating cost of about $62 million, but the department does not administer all the programs themselves. For example, the Department of Community Health administers the Medicaid program, and the Department of Early Care and Learning administers the subsidized childcare program.

Integrated eligibility systems are far more convenient for the customers, requiring them to enter only one door, instead of up to five separate doors in the case of Georgia. It also streamlines the application process for the customer.

On the administrative side, all the hard work is done behind the scenes. The automated systems can share information between programs. Moreover, the technology sets up the state to accomplish future streamlining, consolidation, and reform.

Despite all these advantages of the Gateway, there is still room for improvement. Take Utah’s system, for example.

Utah’s Integrated System

Although Georgia is ahead of many states, Utah may be the furthest ahead.

As explained in a recent American Enterprise Institute report, Utah streamlined 23 workforce programs across six state agencies into a Department of Workforce Services.

In addition to helping customers with employment, Utah treats basic welfare programs as support services. These include food stamps, subsidized childcare, financial assistance, and medical programs. Customers also can file claims for unemployment insurance and apply for disability services.

The Utah system is clean and easy for the customer. Its “no wrong door” policy allows easy access to help in finding employment and receiving support services. It also sends a clear message that Utah prioritizes work as a solution.

Behind the scenes, Utah works with various federal agencies to make the system work. It is not an easy task. It requires creative solutions and continual effort on part of the state to take on the many hassles that come with dealing with the federal government, including the burdensome task of securing “waiver” approvals to federal law from the federal agencies.

However, the goal is worthwhile. It creates an easier experience for the customers, at overall less administrative cost.

Much More Work Needs to Be Done

Utah is showing the way, but much more work needs to be done.

There are still welfare benefits that the federal government does not allow states to administer. These program benefits are additional doors that people must enter, requiring additional effort to apply for those benefits and hoops to jump through to get assistance.

In other words, while Georgia has integrated eligibility systems, and Utah has gone even further with its integration, there are federal government programs outside the control of the states. These include the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Supplemental Security Income, and public housing.

Furthermore, as we have written about, the rules themselves still need fixing to eliminate welfare cliffs and marriage penalties.

Nevertheless, progress is being made, and the work continues on.

Do you have experience with the Georgia Gateway and other assistance programs? Or perhaps experience in another state? Share your experiences in the comments below.

List of Programs per the Government Accountability Office, Reports GAO-15-516 and GAO-19-200.

- 21st Century Community Learning Centers

- Additional Child Tax Credit

- Adoption Assistance

- Adult Education Grants to States (Adult Education and Family Literacy Act)

- Affordable Care Act Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program

- American Indian Vocational Rehabilitation Services

- Career and Technical Education – Basic Grants to States

- Chafee Foster Care Independence Program

- Child and Adult Care Food Program (lower-income components)

- Child Care and Development Fund

- Child Support Enforcement

- Choice Neighborhoods Implementation Grants

- Commodity Supplemental Food Program

- Community Based Job Training Grants

- Community Development Block Grants

- Community Service Employment for Older Americans

- Community Services Block Grant

- Compensated Work Therapy

- Consolidated Health Centers

- Disabled Veterans’ Outreach Program

- Earned Income Tax Credit

- Education for the Disadvantaged- Grants to Local Educational Agencies (Title I, Part A)

- Emergency Food and Shelter Program

- Environmental Workforce Development and Job Training Cooperative Agreements (Brownfield Job Training Cooperative Agreements in 2011report)

- Exclusion of Cash Public Assistance Benefits

- Family Planning

- Federal Pell Grants

- Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants

- Federal TRIO Programs

- Federal Work-Study

- Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations

- Foster Care

- Foster Grandparent Program

- Fresh Fruits and Vegetables Program

- Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs

- Grants to States for Workplace and Community Transition Training for Incarcerated Individuals

- H-1B Job Training Grants

- Head Start

- Higher Education: Aid for Institutional Development programs and Developing Hispanic-Serving Institutions programs

- HOME Investment Partnerships Program

- Homeless Veterans’ Reintegration Program (Homeless Veterans’ Reintegration Project in 2011 report)

- Homeless Assistance Grants

- Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS

- Improving Teacher Quality State Grants

- Indian and Native American Program (Native American Employment and Training in 2011 report)

- Indian Education – Bureau of Indian Education

- Indian Education—Formula Grants to Local Educational Agencies

- Indian Health Service

- Indian Housing Block Grant

- Indian Human Services (Division of Human Services)

- Job Corps

- Job Placement and Training Program (Indian Employment Assistance in 2011 report)

- Job Training, Employment Skills Training, Apprenticeships, and Internships

- Legal Services Corporation

- Local Veterans’ Employment Representative Program

- Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program

- Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

- Maternal and Child Health Block Grant

- Mathematics and Science Partnerships

- d settings.

- Medicaid

- Medical Care for Low- Income Veterans Without Service-Connected Disability

- Migrant and Seasonal Farmworker Program

- National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program

- National Farmworker Jobs Program

- National School Lunch Program (free and reduced- price components)

- Native American Career and Technical Education Program (Career and Technical Education – Indian Set-Aside in 2011 report)

- Native Employment Works (Tribal Work Grants in 2011)

- Native Hawaiian Career and Technical Education Program

- Nutrition Assistance Program for Puerto Rico

- Nutrition Service for the Elderly

- Older Americans Act Grants for Supportive Services and Senior Centers

- Older Americans Act: National Family Caregiver Support Program

- Projects with Industry

- Public Housing

- Reentry Employment Opportunities (Reintegration of Ex-Offenders in 2011 report)

- Refugee and Entrant Assistance – Discretionary Grants (Refugee and Entrant Assistance – Targeted Assistance Discretionary Program from 2011 is now part of this program)

- Refugee and Entrant Assistance – Targeted Assistance Grants

- Refugee and Entrant Assistance – Voluntary Agencies Matching Grant Program

- Refugee and Entrant Assistance State/Replacement Designee Administered Programs ((Refugee and Entrant Assistance – Social Services Program from 2011 is now part of this program)

- Registered Apprenticeship

- Rental Housing Bonds Interest Exclusion

- Rural Education Achievement Program

- Rural Rental Assistance Payments

- Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program

- School Breakfast Program (free and reduced-price components)

- Second Chance Act Technology-Based Career Training Program for Incarcerated Adults and Juveniles (Second Chance Act Reentry Initiative in 2011 report)

- Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers

- Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance

- Senior Community Service Employment Program

- Social Services and Targeted Assistance for Refugees

- Social Services Block Grants

- Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC)

- State Children’s Health Insurance Program

- State Supported Employment Services Program

- State Vocational Rehabilitation Services Program (Rehabilitation Services – Vocational Rehabilitation Grants to States in 2011 report)

- Summer Food Service Program

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- Supplemental Security Income

- Supportive Housing for Persons with Disabilities

- Supportive Housing for the Elderly

- Tech Prep Education State Grants

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

- The Emergency Food Assistance Program

- Title I Migrant Education Program

- Trade Adjustment Assistance for Workers

- Transition Assistance Program

- Transitional Cash and Medical Services to Refugees

- Tribal Technical Colleges (United Tribes Technical College in 2011 report)

- Tribally Controlled Postsecondary Career and Technical Institutions

- Veterans Pension and Survivors Pension

- Veterans’ Workforce Investment Program

- Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment (Vocational Rehabilitation for Disabled Veterans in 2011 report)

- Voluntary Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit- Low-Income Subsidy

- Wagner-Peyser Act Employment Service (Employment Service/Wagner-Peyser Funded Activities in 2011 report)

- Water and Waste Disposal Systems for Rural Communities

- Weatherization Assistance

- Work Opportunity Tax Credit

- Workforce Investment Act Adult Activitiesa

- Workforce Investment Act Youth Activitiesb

- WIOA National Dislocated Worker Grants (WIA National Emergency Grants in 2011)

- WIOA Youth Program (WIA Youth Activities in 2011 report)

- Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional Occupations

- Youth Partnership Programs (Conservation Activities by Youth Service Organizations in 2011 report)

- YouthBuild

DISINCENTIVES FOR WORK AND MARRIAGE IN GEORGIA’S WELFARE SYSTEM

Based on the most recent 2015 data, this report provides an in-depth look at the welfare cliffs across the state of Georgia. A computer model was created to demonstrate how welfare programs, alone or in combination with other programs, create multiple welfare cliffs for recipients that punish work. In addition to covering a dozen programs – more than any previous model – the tool used to produce the following report allows users to see how the welfare cliff affects individuals and families with very specific characteristics, including the age and sex of the parent, number of children, age of children, income, and other variables. Welfare reform conversations often lack a complete understanding of just how means-tested programs actually inflict harm on some of the neediest within our state’s communities.