by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Jan 29, 2015

Successful reentry for those coming home from prison is a concept that is not easily defined.

Most often, success is defined in terms of low recidivism – that is, fewer people who return to prison within three years of their release. However, simply measuring successful reentry in terms of recidivism does not present a complete picture of what it means to successfully reintegrate. There is much more to it than a person simply not ending up back in prison. To gain a more complete picture of what it means to successfully reintegrate into society – into a community, a family, and a faith – it is helpful to a look at a real-life example of someone who has done it.

Meet Tony Kitchens – a husband, father, son, and brother – who spent 12 years behind bars in Georgia during the 1970s and 1980s. Today, Tony is an Evangelism Catalyst with the North American Mission Board (NAMB) and has consulted with the Governor’s Office of Transition, Support, and Reentry (GOTSR).

He is celebrating thirty years of successful reintegration this January 2015 – a journey which he says is still continuing to this day.

In honor of Tony’s thirty years of successful reintegration, Walker Faith and Character Based Prison in Northwest Georgia held a Reentry Celebration for him on January 9, 2015. The celebration provided the opportunity for family, friends, coworkers, non-profit leaders, Department of Corrections (DOC) staff, the residents of Walker and the Governor’s Office to recognize Tony for his successful journey of navigating reentry to reintegration; it also provided Tony a wonderful opportunity to give current inmates a picture of what is possible for their lives.

Tony – who was once an inmate at Walker State Prison – brings a unique perspective that carries a lot of weight among the men at Walker. He has the ability to address them as one who was once in their shoes; one who mopped the same floors they now mop and slept in the same cells they sleep in.

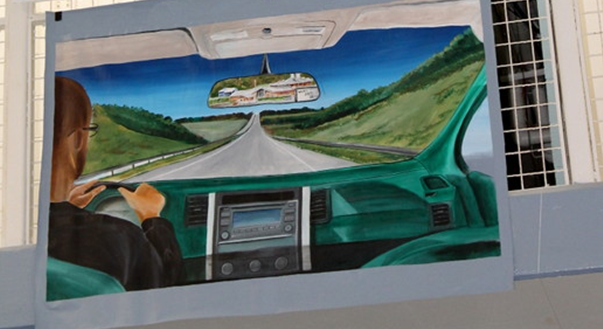

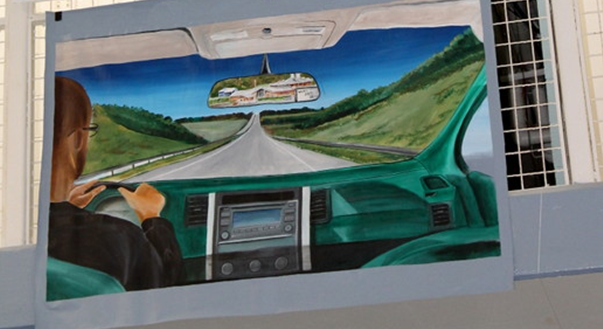

The Reentry Celebration took place in the prison cafeteria – a large space filled with hundreds of inmates dressed in white uniforms and nearly fifty guests. Above the stage hung large banners with seals from various state agencies, along with canvases painted by the inmates that included the seal of Walker Faith and Character Based Prison, the North American Mission Board LoveLoud logo, and a creative rendering of a line Tony is often heard quoting:

“I keep the penitentiary in my rear view and what lies ahead in my pre-view.”

A quartet comprised of inmates from Walker opened the celebration by singing the national anthem. The performance astounded everyone, including Jay Neal, Executive Director of the Governor’s Office of Transition, Support, and Reentry (GOTSR), who commented that Super Bowls do not have performers who sing as well as they did. This performance was followed by an introduction of the speakers and a powerful recitation of the “Brothers Creed” in which hundreds of inmates pledged to live exemplary lives of character while in prison and once they are released into the community.

Jay Neal followed as the first of a several speakers who would present at the event. Neal spoke about the first step required for successful reintegration, which is having accountability in one’s life. He reflected on his own experience as a young man and learning the need to have accountability in place before entering the pastorate. He encouraged the inmates in attendance to take this same measure in their own lives, as it is an important aspect of living a life of good character.

The next speaker, Tony Lowden, a pastor and Project Coordinator for the Prison In-Reach Grant for the Georgia Prisoner Reentry Initiative (GA-PRI), built upon the principle of accountability and spoke about possibility. He recalled the biblical figure David and his calling to be a king, explaining that David had to first experience time hiding from his enemies in the Adullam Cave before he ascended to the throne. He paralleled this experience to inmates’ time in prison, calling it their “Adullam Cave,” and encouraged them to dream of being who they are meant to be – leaders of their families and communities.

Following Mr. Lowden, one of the inmates from the quartet sung R. Kelly’s “I Believe I Can Fly,” while another played the piano. The performance inspired the entire room and several shouts of approval could be heard from among the hundreds of inmates sitting in attendance.

Brenda McGowan, Southeast Regional Director for Prison Fellowship, came on deck third and highlighted the importance of sustainability for successful reintegration. Touching on the life of Chuck Colson and Tony Kitchens, a Colson scholar, she discussed how a transformed life is the only way a person can face the difficulties of reintegration without losing hope.

Last of all, Tony Kitchens delivered the keynote address which tied the entire message together. He drove home the point that reentry is a destination whereas reintegration is a journey. He compared reintegration to the game of baseball and explained that it is not ultimately about hitting a home run; rather, it is a day-by-day process that is slow and much more like advancing from one base to the next. First base is becoming accountable, second base is seeing and believing what is possible, and third base is sustaining that vision through a spiritual transformation of the mind and heart.

“Reentry is a destination whereas reintegration is a journey.”

Upon finishing, Tony received a standing ovation. He was presented with a personal letter from Governor Nathan Deal commending him for his excellent example for returning citizens and Georgians at large. Tony was also presented with a beautifully crafted grandfather clock that a group of inmates made out of recycled material from Walker prison – an excellent representation of Tony’s life in the way he has “redeemed the time” and used his gifts well in the community. The clock reads, “Celebrating 30 Years Free” on the front glass pane.

It was clear that the inmates at Walker were glad to see someone who is overcoming the collateral consequences of incarceration. Tony’s life serves as a powerful testimony to the redemption that is possible for returning citizens, and his message gives them hope that they can experience the same.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Dec 15, 2014

GCO’s latest report provides solutions that aim to minimize the role debt has in driving recidivism rates.

Offenders often leave prison owing tens of thousands of dollars in debt, creating serious obstacles to a successful reentry. The state expects returning offenders to pay these debts, though many struggle to simply find a job and a place to live.

Studies have shown average debt amounts in certain jurisdictions in the U.S. to be as high as $20,000 in child support arrears and between $500 and $2,000 in offense-related debt. Carrying an onerous amount of debt and having to immediately repay it puts tremendous financial pressure on recently released offenders. They face the threat of having their driver’s license suspended, having their wages garnished, and being re-incarcerated for failing to pay their obligations. These sanctions can discourage them from seeking legitimate employment and drive them to participate in the underground economy, leading them on a pathway back to prison.

Today, Georgia Center for Opportunity released a report titled A High Price to Pay: Recommendations for Minimizing Debt’s Role in Driving Recidivism Rates, which outlines several steps the state can take to encourage returning citizens to pay current obligations and repay debts in a realistic manner. Such action should result in more money going to support children and victims and result in fewer people ending up back behind bars.

The report’s recommendations include:

- Identify offenders with child support involvement upon entry to prison

- Provide child support information and services to parents during their incarceration

- Provide a 90-day grace period before indigent returning citizens have to pay their obligations and repay debts to ease the transition phase

- Limit the amount of wages to be garnished by the state

- Forgive fines, fees, and surcharges owed to the state for consistent payments of child support and restitution

- Reinstate driver’s licenses that were suspended for non-payment of child support

- Forgive arrears and interest owed to the state for a set number of consecutive payments of current child support***

- Designate a single agency to track and consolidate returning citizens’ debts

GCO will post a series of blogs that highlight different sections of the report, including the various factors that cause offenders to accrue debt, the effect debt can have in driving recidivism rates, and an in-depth look at the recommended policies.

Read the full report: A High Price to Pay: Recommendations for Minimizing Debt’s Role in Driving Recidivism Rates

***Edit to the report: May 6, 2015

At the time of writing the report, the author was unaware that Georgia already has a detailed debt reduction program in place to assist indigent non-custodial parents who owe arrears to the state. The Division of Child Support Services’ (DCSS) State Debt Reduction Program (SDRP) provides non-custodial parents the ability to have a significant percentage of their state-owed arrears reduced if an agent determines that:

(1) “Good cause” existed for the nonpayment of the public assistance debt;

(2) Repayment or enforcement of the debt would result in substantial and unreasonable hardship for the parent owing the debt;

(3) The non-custodial parent is currently unable to pay the debt;

(4) The non-custodial parent is making regular payments of current child support, regardless of the amount.

The amount that eligible non-custodial parents can have their arrears reduced depends upon the amount they owe. Those with a greater amount of arrears owed to the state are eligible to have a greater percentage reduced (with the exception of those who owe less than $100, who can have their entire state-owed arrears balance waived). For example, non-custodial parents with state-owed arrears balances of $9,000 or greater can have their arrears waved or reduced by 75 percent, so long as they pay the remaining 25 percent owed in a lump sum payment or in 24 monthly installments.[i]

While Georgia has a detailed debt reduction program in place, it appears that the participation in the program is limited. In 2014, only 349 out of the 354,427 total non-custodial parents ordered to pay child support in Georgia entered into the plan, based on the 30 DCSS offices that reported.[ii]* More should be done to enroll struggling returning citizens with child support arrears owed to the state into the program. One way the state can do this is by promoting it within the Fatherhood Program and Child Support Problem Solving Courts (PSCs), which returning citizens will be likely to participate in.

Sources:

[i] Division of Child Support Services, “State Debt Reduction Guidelines,” Employee Reference Guide – Standard Operating Procedure 251, Email Release May 24, 2013.

[ii] Erica Thornton, Manager of the Policy and Paternity Unit, Division of Child Support Services, Georgia Department of Human Services, email message to author, February 3, 2015; Georgia Department of Human Services, “Division of Child Support Services: Fact Sheet,” Revised November 2014.

*While not all 354,427 non-custodial parents ordered to pay child support in Georgia owe arrears to the state, the large figure suggests that there may be numerous non-custodial parents (particularly those reentering society from prison) who do (or should) qualify for the program, but are currently being overlooked.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Nov 12, 2014

Professional License Restrictions

Those who have “been convicted of any felony or of any crime involving moral turpitude in the courts of this state or any other state, territory, or country” are subject to having their application denied on account of their conviction.[i] This restriction severely curtails the number of professions available to people coming out of prison, many of which offer considerable promise for returning citizens given the vocational training they received in prison.

As it stands now, nearly 80 professions are off-limits to those with a felony conviction, including becoming a barber, cosmetologist, electrical contractor, plumber, conditioned air contractor, auctioneer, utility contractor, registered trade sanitarian, and scrap metal processor, among others.[ii]

Lift Restrictions and Open-Up Job Opportunities

In order to open-up a greater range of professions for returning citizens, the state of Georgia should lift blanket restrictions on professional licenses. Some of the professions most suitable to returning citizens’ skillsets are currently inaccessible to them because they are barred from acquiring a license in those professions. These blanket restrictions should be replaced with reasonable criteria for determining whether a given profession is suitable for a person given his or her criminal history.

As is the case for determining whether any particular job is suitable for a person given his or her felony conviction, professional licensing boards should consider the following factors in determining whether the granting of a license is appropriate:

- The nature of the crime committed and its relation to the license sought

- The time elapsed since the crime

- The applicant’s age at the time of the crime

- The evidence that the applicant has been rehabilitated[iii]

By using these criteria, professional licensing boards can eliminate unreasonable licensing restrictions while ensuring that public safety is protected. A person might be restricted from obtaining a license in one profession due to the nature of his or her crime, but prove to be an excellent candidate for receiving a license in numerous other professions where his or her crime is unrelated. These decisions must always be determined on a case-by-case basis, just as they are for applicants without a felony conviction.

A Look at Other States

Many states are already working toward increasing opportunities for those with felony convictions to obtain professional licenses. Currently, “21 states have standards that require a ‘direct,’ ‘rational,’ or ‘reasonable’ relationship between the license sought and the applicant’s criminal history to justify the agency’s denial of a license.”[iv]

- Colorado law mandates that a felony conviction or other offense involving “moral turpitude” cannot, in and of itself, prevent a person from applying for and receiving an occupational license.[v]

- New Mexico only allows occupational licensing authorities to disqualify applicants from felony or misdemeanor convictions involving “moral turpitude” if they are directly related to the position or license sought.[vi]

- Connecticut requires a state agency to first consider the relationship between the offense and the job, the applicant’s post-conviction rehabilitation, and the time elapsed since conviction and release before determining a person is not suitable for a license.[vii]

- Louisiana forbids licensing agencies from disqualifying a person from obtaining a license or practicing a trade solely because of a prior criminal record, unless the conviction directly relates to the specific occupation. In the event the applicant is denied because of a conviction, the reason for the decision must be made explicit in writing.[viii]

Conclusion

Enabling people with felony convictions to acquire professional licenses in Georgia would benefit a variety of stakeholders. Not only would it give returning citizens greater access to a variety of occupations and enable them to support themselves and their families, it would also make the most of current job-training programs offered in state prisons, create opportunities for expansion and partnership with technical schools, and enable offenders to maximize their time in prison and develop transferable job skills. Together, these advantages would work to reduce recidivism, utilize taxpayer dollars more efficiently, and promote public safety in Georgia.

Image credit: Wrightsville Beach Plumbing (featured image) and Mahanomi Health and Beauty Care Info

[i] O.C.G.A. § 43-1-19; italics added.

[ii] O.C.G.A. §§ 43-1 to 43-51.

[iii] Legal Action Center, “Recommended Key Provisions,” para. 6, https://www.lac.org/toolkits/standards/ Key%20Provisions%20-%20Standards.pdf.

[iv] Legal Action Center, “Standards for Hiring People with Criminal Records,” Advocacy Toolkits to Combat Legal Barriers Facing Individuals with Criminal Records, accessed November 29, 2013, para. 8, https://www.lac.org/toolkits/standards/standards.htm.

[v] Colo. Rev. Stat. § 24-5-101; Legal Action Center, “Overview of State Laws that Ban Discrimination by Employers,” 2, https://www.lac.org/toolkits/standards/Fourteen_State_Laws.pdf.

[vi] Legal Action Center, “Overview of State Laws,” 3.

[vii] Ibid., 1.

[viii] La. Rev. Stat. § 37:2950.

This post was adapted from Georgia Center for Opportunity’s December 2013 report titled Increasing Employment Opportunities for Ex-Offenders.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Nov 5, 2014

Governor Nathan Deal

Georgia is receiving national attention as the state recently received four competitive federal grants from the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) to implement its Prisoner Reentry Initiative (GA-PRI). Georgia is the only state to have received all four grants at one time – a testament to the smart framework that the state has developed to bring about significant reductions in recidivism.

The Governor’s Office of Transition, Support and Reentry (GOTSR) developed the GA-PRI Framework with the assistance of the Center for Justice Innovation last fall and began taking steps to implement it at five pilot sites around the state. GOTSR took these steps knowing that additional funding would be necessary to successfully carry out this initiative.

The office applied for the BJA grants around the beginning of summer with the hopes that it would receive the funding necessary to hire the right staff, provide evidence-based training and implementation, improve information sharing and measuring outcomes, and establish quality assurance mechanisms.

Jay Neal, executive director of GOTSR, explained that the office applied for the grants with the expectation that each one would fund a different component of the initiative and build on each other. This created a package deal that would enable the state to fully implement the GA-PRI framework without duplicating funds. This smart strategy appealed to BJA, who awarded the office each grant for which it applied.

The four grants that Georgia received for this initiative include:

| Smart Supervision Grant |

Department of Corrections; Governor’s Office of Transition, Support and Reentry |

$750,000 |

| Statewide Recidivism Reduction Grant |

Department of Corrections; Governor’s Office of Transition, Support and Reentry |

$3,000,000 |

| Justice Information Sharing Solutions Grant |

Criminal Justice Coordinating Council |

$498,234 |

| Justice Reinvestment: Maximizing State Reforms Grant |

Department of Corrections; Governor’s Office of Transition, Support and Reentry |

$1,750,000 |

Now that the state has received these grants, the next challenge will be to put all of its planning into action. This implementation phase will be critical to the success of prisoner reentry reform in Georgia, and the state understands that it will take collaboration among all stakeholders in the community for it to be successful, including businesses, churches, educational institutions, non-profits, and others.

GOTSR will be presenting its three year implementation strategy at the Justice Reinvestment National Summit in San Diego (November 17-19, 2014) where hundreds of people from over 30 states will be represented. These states will be looking at Georgia to see how well the state can implement its new reentry framework to reduce recidivism.

Georgia’s goal is to see a decrease in recidivism by seven percent in two years, and by 11 percent over five years.

Jay Neal, Executive Director of the Governor’s Office of Transition, Support and Reentry

The momentum for reform is strong right now in Georgia, but the true test of the state’s commitment to preparing citizens for successful reintegration will have to be seen in the coming years as the inevitable difficulties of implementation arise.

For now, the state’s leaders seem prepared to face those challenges as they arise. There is a prevailing optimism that can be heard in government boardrooms and local reentry coalitions around the state, especially as people recount the incredible progress that has been made in Georgia over the last four years in the area of criminal justice reform.

Image credit: The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (featured image), The Wall Street Journal, and The Polk Fish Wrap

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Oct 24, 2014

Employers have a responsibility to make sure the person they hire for a position is a right fit for the job. Background checks are one important part of this process, as they help to determine whether a particular industry or position is suitable for an applicant with a certain criminal history. However, it is vital that criminal records are used properly and not discriminatorily.[i] They should not be used as a screening tool to automatically dismiss all applicants with felony convictions. Rather, they should be used in a discerning manner, causing an employer to examine whether a person’s criminal history has any relation to the position sought. If there is a strong correlation, then there may be reasonable grounds to remove the applicant from consideration. If not, the applicant deserves the same chance as any person to demonstrate his or her qualifications for a job.

What does it mean to “ban the box”?

“Banning the box” refers to removing the question about a person’s criminal history from the initial job application and postponing the question to a later point in the hiring process. This policy increases the likelihood that a person with a criminal record will get hired by giving the applicant an opportunity to demonstrate his or her qualifications for a job without automatically being screened from the hiring process.

Postponing the question of an applicant’s criminal history to a later point in the hiring process allows applicants to explain their criminal record to an employer in person. This face-to-face interaction is essential to increasing an ex-offender’s chance of becoming employed. It provides an ex-offender the opportunity to be candid about his or her past and to explain how overcoming setbacks have fashioned him or her into a qualified candidate for the position. This conversation gives an employer the chance to listen to the ex-offender’s story, relate to him or her as a person, and get a better grasp of the person’s character and strengths. By giving ex-offenders the opportunity to represent themselves in the best light and to prove how qualified they are for a position, an employer may find his or her best candidate for the job.

Who is “banning the box”?

States, counties, and cities across the nation are establishing fair hiring polices for ex-offenders by “banning the box” on applications for public employment.

As of September 2014, thirty states have a local or state-level “ban the box” fair hiring policy for public employers. Among these states, thirteen have enacted statewide fair hiring laws, and six have also extended the fair chance policy to government contractors or private employers.[ii]

Nationwide, almost seventy cities and counties – including Atlanta and Fulton County – have taken steps to remove barriers to employment for qualified workers with records, and twenty of these cities and counties have extended “ban the box” policies to government contractors or private employers.[iii]

Why should Georgia “ban the box”?

Although the Governor spoke of “banning the box” earlier this year, he has not yet issued an executive order for state employers to do so. Taking this decisive step will be important for continuing the reforms his office has worked so hard to carry out this year to improve outcomes for returning citizens.

By following the precedent set by Atlanta and Fulton County and officially embracing “ban the box” policies for state employers, the state can help more people with criminal records get good jobs for which they qualify. This, in turn, will improve their chance of successfully reintegrating into society, decrease their chance of recidivating, enable them to benefit employers, and allow them to contribute to the economy of the state.

Embracing this policy at the state level will also encourage county, city, and even private employers across Georgia to follow suit.

For proof that “ban the box” policies help people with criminal records get good jobs and benefit employers, check out Durham, NC’s success story by clicking here.

This post was adapted from Georgia Center for Opportunity’s December 2013 report titled Increasing Employment Opportunities for Ex-Offenders.

Image credit: GT L&E Blog (featured image) and Accurate Background, Inc.

[i] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records in Employment Decisions Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” Office of Legal Counsel, April 25, 2012, accessed November 29, 2013, https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/arrest_conviction.cfm.

[ii] National Employment Law Project, Ban the Box: U.S. Cities, Counties, and States Adopt Fair Hiring Policies to Reduce Unfair Barriers to Employment of People with Criminal Records, September 2014, ii, 3, https://www.nelp.org/page/-/SCLP/Ban-the-Box.Current.pdf?nocdn=1.

[iii] Ibid., 1-2.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Sep 29, 2014

Every Georgian is affected by the criminal justice system in some way. Whether it is paying taxes to fund the more than a billion dollars spent on prisons each year or knowing a loved one who has spent time behind bars, the justice system is becoming an increasingly familiar issue in the lives of Georgians.

In 2009, the Pew Center on the States released a report revealing that 1 in 13 adults were under some form of correctional supervision in Georgia. This means that over half-a-million Georgians were either in jail, in prison, on parole, or on probation that year. This percentage far surpassed the national average, which was still an astonishing 1 in 31 adults under correctional supervision.

Even more staggering, 2.6 million people have a criminal record on file with the Georgia Crime Information Center, while the state’s total population is 10 million people. The collateral consequences associated with having a criminal record mean that as many as 1 in 4 Georgians likely face barriers to obtaining employment, housing, and even voting.

Currently, 53,000 people are incarcerated in Georgia, giving the state the fifth highest prison population in the nation. The incarcerated population more than doubled between 1990 and 2011, while the state’s general population increased by only half that rate during the same time period.

The Merry-Go-Round

Once a person enters the system, his or her likelihood of staying in it is fairly strong. The state releases 20,000 prisoners back into the community every year, and 2 out of 3 of those released are rearrested within three years. Nearly 1 in 3 are re-convicted within this time frame, resulting in re-incarceration.

While the state reports a recidivism rate of 30 percent over the past decade (determined by the number of offenders who are reconvicted within three years of release), the actual recidivism rate is closer to 50 percent – taking into account the number of people who commit a technical violation while on probation and parole, as well as the number of offenders who recidivate after the standard three-year time period.

The Cost

The effect of recidivism is very costly to the state: It negatively impacts public safety, results in burgeoning costs to taxpayers, and contributes to the breakdown of families.

Public Safety

Released offenders who continue to have unaddressed criminogenic (crime-producing) needs are likely to re-engage in criminal behavior and place themselves, their families, and their community at risk. Criminal behavior may arise from a substance abuse or mental health issue, from negative peer associations, from a poor family environment, from desperation caused by their inability to meet their basic needs for housing, employment, and transportation, and from a variety of other risk factors. Without addressing the underlying factors that lead returning citizens to engage in criminal behavior, the recidivism rate will continue to remain high as new crimes and technical violations of probation and parole are committed.

Taxpayers

Recidivism places a heavy burden on taxpayers. The cost to incarcerate one person for a year in Georgia is $21,000 – more than twice the amount the state spends toward educating one student for a year. This means that every cohort of released prisoners that recidivates amounts to $130 million annually, given the 30 percent recidivism rate and the 20,000 offenders released each year. Further, state expenditures on incarceration reached $1.1 billion in fiscal year 2010 – more than twice the amount spent in 1990, which was $492 million. For the amount taxpayers have spent on the prison system in recent years, the outcomes have been unacceptable.

Families

Finally, a person cycling in and out of prison creates instability in the life of his or her family. Significantly, 60 percent of inmates in Georgia are parents, and a number of these parents have been incarcerated more than once. Children of incarcerated parents are more likely to perform poorly in school, to be exposed to their parent’s substance abuse, to use drugs, to experience mental health issues, to experience domestic violence, and to live in poverty. Incarceration puts a tremendous strain on existing relationships, decreases the chances that partners will marry, transforms family roles, and often leads custodial parents to depend on public assistance. Families experience shame, anger, hurt, and despair at the incarceration of loved ones, creating inner turmoil that is often never addressed.

What Can Be Done?

Because of the enormous costs posed by incarceration and recidivism, it is essential for Georgia to promote solutions that will address underlying issues returning citizens face. This effort must take place at all points along the continuum, from the Governor’s Office down to individuals in the community.

Several areas of reform that Georgia Center for Opportunity’s Prisoner Reentry Working Group has addressed to improve reentry outcomes involve increasing employment opportunities (read report), restructuring debt, and developing the criminal justice and service provider workforce.

Employment

Employment plays a critical role in reducing offender recidivism, as it has the power to deter ex-offenders from crime and incentivize law-abiding behavior. Key barriers to employment that the working group identified include driver’s license suspensions, missing identification (i.e., Social Security cards and birth certificates), professional license restrictions, and employers’ negative perceptions.

To remove these barriers, the group recommended that the state lift suspensions on driver’s licenses for people who committed a non-driving related drug offense, offer incentives to employers to hire those with a criminal record, and have public and private employers postpone the question about an applicant’s criminal history to a later point in the interview process. Several of these recommendations were signed into law in April 2014.

Debt

Various state agencies enforcing the payment of debts and obligations without considering the needs and financial circumstance of returning citizens can lead them to recidivate. Returning citizens often carry excessive debt because of missed child support payments that accrue during their incarceration, court-imposed fees, fines, and surcharges for their offense, unpaid restitution, and the inability for them to earn money while in prison.

Several steps that the state can take to encourage returning citizens to repay this debt in a realistic manner include: Identifying offenders with child support orders upon entry to prison; providing offenders with pertinent information about their child support responsibilities; providing a grace period of 90 days upon release that gives returning citizens the opportunity to find a job and get back on their feet; and providing incentives for returning citizens to pay current obligations of child support and restitution by forgiving a portion of fines, fees, surcharges, and child support arrears owed to the state.

Workforce Development

There is an urgent need for the criminal justice workforce and community service providers to be trained in delivering evidence-based programs and practices. Without proper training and implementation, Georgia’s recidivism rate is likely to remain unchanged.

The state can better ensure successful reentry outcomes are reached by providing training and support to agencies and service professionals in the use of evidence-based practices, developing a hybrid degree program that combines criminal justice training and case management techniques, ensuring a risk/needs assessment is used and followed from entry into prison to treatment in the community, providing the workforce the ability to use graduated sanctions and incentives, and providing accountability to the workforce to ensure evidence-based practices are being used.

Conclusion

Each person involved with this reentry effort, from the governor to mentors in the community, need to put into practice what has shown to work in reducing recidivism. This effort will require education, training, resources, and coordination on all fronts, and it is one that should be pursued with fidelity. Doing so will help to bring restoration to families, build stronger communities, and ensure a more just society.

Click here to view The State of Corrections infographic

Page 6 of 8« First«...45678»