by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Apr 1, 2015

We are happy to provide you with this update on some of the bills that GCO is following this session. Should you have any questions or comments, please email Eric Cochling.

House Bill 243 – Education Savings Accounts – sponsored by Rep. Mark Hamilton, R-Cumming

The ESA Bill (HB 243) did not make it onto the House floor for a vote before the end of Crossover Day. What that means, practically speaking, is that the bill is likely dead for the session.

Because Georgia runs on a biennial cycle, bills that made progress this year will pick up where they left off starting in the 2016 legislative session. This means that we are in a good position for January 2016 since we have a bill that has been vetted and has made significant progress in the House. We also feel confident that, given the broad and bipartisan support for the bill within the general assembly and overwhelming support among Georgia voters, our chances for passing the bill next session are excellent.

While this is disappointing news, we encourage you to continue to speak about the importance of educational choice (and ESAs specifically) with your legislators throughout the year! If you don’t know who your legislators are, find them here.

To learn more about ESAs and to support Rep. Hamilton and Sen. Hunter Hill, who is sponsoring similar legislation in the state senate, visit www.foropportunity.org/go/esa.

Senate Bill 133 and Senate Resolution 287 – Opportunity School Districts (OSD) – carried by Senator Butch Miller

The governor’s signature legislation is moving forward despite unexpected opposition and difficulty. Senate Bill 133 provides the nuts and bolts of how the OSD would operate, while Senate Resolution 287 allows voters to decide in 2016 whether they are willing to entrust new powers to the governor’s appointed OSD superintendent to take over failing schools. Each passed with the requisite constitutional majority, 108-53 and 121-47, respectively.

Senate Resolution 287 will ask voters:

“Shall the Constitution of Georgia be amended to allow the state to intervene in chronically failing public schools in order to improve student performance?”

There was lots of fiery rhetoric throughout the committee hearings and on the House floor both for and against the resolution. Opponents argue that the bill would allow for power to be taken away from local school boards and placed in the hands of a centralized bureaucracy. Supporters maintain that decision‑making power in an OSD is decentralized away from the local school board bureaucracy, and transferred to individual school principals, teachers, and, often, charter school boards.

In other words, both sides argue that they support local control.

At first glance it is difficult to see how a state takeover could lead to more local involvement, but with New Orleans as an example, we can now imagine a way for government to create the space and, importantly, the pressure needed for local communities and institutions to address problems plaguing our most chronically failing schools.

House Bill 440 – Business and Education Succeeding Together (BEST) – sponsored by Rep. Mike Glanton, D- Jonesboro

In February, Rep. Mike Glanton (D) introduced a bill that would create a separate corporate-only tax credit program (Business and Education Succeeding Together, or BEST) that would provide $12 million in scholarship funding. The program is separate from the current tax credit scholarship program and has many of the accountable provisions that the current program lacks. While the bill has not made much progress this session, we believe it will be seriously considered next session as an additional way to continue expanding opportunities for students and families in the state.

Senate Bill 129 – Religious Freedom Restoration Act – Sponsored by Rep. Josh McKoon – R – Columbus

SB 129, the religious liberty bill, was “tabled” by the House Judiciary Committee, because of an amendment that would have effectively gutted the bill of its purpose.

The so-called “non-discrimination” clause introduced by state Rep. Mike Jacobs, R-Brookhaven, “completely undercut the purpose of the bill,” McKoon said. Supporters of the bill felt that adding this clause, which the majority of the thirty plus state RFRA’s and the federal RFRA do not have, would effectively leave religious liberty worse off in the state of Georgia. For example, adding a non-discrimination clause could prevent private religious schools from discriminating based on religious belief when hiring staff.

SB 129 became part of a larger culture war, and its failure – tabling the bill makes it very unlikely that it will reach a House floor vote before the end of the session – was due in large part to the fear of “perception” rather than the reality of the purpose or language of the bill. The ongoing struggle over Indiana’s new law is certainly not encouraging lawmakers here to act.

Read additional commentary on the RFRA legislation on our website.

For the case in favor of Georgia’s legislation, read what these fourteen law professors had to say.

Senate Bill 8 and Senate Resolution 7 – Safe Harbor/Rachel’s Law Act – sponsored by Sen. Renee Unterman, R-Buford

Georgia legislators, led by Sen. Renee Unterman, R-Buford, are seeking to tighten Georgia’s existing sex trafficking laws. The combination of Senate Bill 8 and Senate Resolution 7 would help create a new Safe Harbor for Sexually Exploited Children Fund, using new $2,500 fines on convicted traffickers and an annual $5,000 fee on adult entertainment establishments to raise money for the fund. SB 8 sets out the framework of the proposal while SR 7 seeks amendment to the Georgia Constitution by asking Georgians for permission to create the new fund. A governor-appointed commission would manage this fund and the effort.

This money would then be used to pay for physical and mental health care, housing, education, job training, child care, legal help and other services for sexually exploited victims. In addition to the new fines, the Bill would require convicted traffickers be listed on the state sex offender registry – something which surprisingly doesn’t happen now.

Legislators are working together to merge Unterman’s version of the proposal with a similar House version, HB 244, with hopes to assure final passage. The Bill passed through the Senate on a 52-3 vote, and is now working its way through the House Committee for Juvenile Justice.

UPDATE: Both of these bills were voted on Tuesday, March 31st, and passed 150-22 and 151-18, respectfully.

Senate Resolution 80 – Demand Revision of College Board of AP U.S. History – Sponsored by Sen. William Ligon Jr., R-Brunswick

This resolution demands revision by the College Board of Advanced Placement U.S. History. Since approximately 14,000 Georgia students take the College Board’s Advanced Placement U. S. History course each year, the General Assembly is right to be concerned that the new framework “reflects a radically revisionist view of American history that emphasizes negative aspects of our nation’s history while omitting or minimizing positive aspects,” presenting, “a biased and inaccurate view of many important themes and events in American history, including the motivations and actions of seventeenth to nineteenth century settlers, the nature of the American free enterprise system, the course and resolution of the Great Depression, and the development of and victory in the Cold War.” Though the college board denies any political intent, the course content does seem to have a strong bias that focuses on negative aspects of American history, while not presenting much on America’s positive role in the world.

Those in favor of Senate Resolution 80 hope that by acknowledging this problem, other companies might form to challenge the bias of the College Board’s monopoly on Advanced Placement courses for high school students.

UPDATE: This bill, in substitute form, was voted out of the senate prior to crossover day and awaits action by the house.

House Bill 677 and House Resolution 807 – Allowing Casino Gambling in Georgia – sponsored by Rep. Ron Stephens, R-Savannah

For the last several years, some form of gambling has been proposed by various legislators under the guise of saving the HOPE Scholarship. This years’ effort is being sponsored, in part, by Rep. Ron Stephens. House Resolution 807 would place a constitutional amendment on the 2016 ballot that would empower the state to license casinos (which is currently prohibited by the Georgia Constitution), while House Bill 677 is a 127-page bill that describes in detail how the new gambling marketplace in Georgia would operate. These bills, like those in previous years, are being promoted on the basis of the jobs casinos could create, along with the revenue promised to the HOPE Scholarship program. Missing from the analysis is any reference to the problems associated with casinos – including increased levels of addiction and negative economic effects.

House Bill 1 – Haleigh’s Hope Act – sponsored by Rep. Allen Peake, R- Macon

Last Friday, Gov. Nathan Deal signed an executive order directing state agencies to prepare for the enactment of House Bill 1 which authorizes the limited use of cannabis oil to treat eight specific disorders that include cancer, Lou Gehrig’s disease, Crohn’s disease, mitochondrial disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, sickle cell disease, and seizure disorders as long as a physician prescribes the medication. The bill also allows for clinical trials to further study how the drug works.

House Bill 439 – Georgia New Markets Jobs Act – sponsored by Rep. Jason Shaw, R- Lakeland

In 2000 the U.S. Congress created the federal New Markets Tax Credit as an effort to stimulate private investment within poor urban and rural areas. Since 2000 a handful of states followed with their own versions of the law. House Bill 439, Georgia New Markets Jobs Act is another such effort.

According to the New Markets Tax Credit Coalition, the tax credits, “stimulate private investment and economic growth in low income urban neighborhoods and rural communities that lack access to the patient capital needed to support and grow businesses, create jobs, and sustain healthy local economies.”

House Bill 439 would allow for millions of dollars in private investment toward projects and communities that likely would never have received such injections of patient capital otherwise – stimulating economic growth in low-income neighborhoods. In other states this tax credit has been used to finance everything from health care centers to charter schools, groceries in food deserts, community centers, domestic violence shelters, factories and small business loan funds in distressed urban, suburban and rural communities.

HB 439 passed through the Senate last Friday 41-9. Though HB 439 differs from the federal New Markets Tax Credit, this bi-partisan sponsored bill represents innovative policy that seeks to remove barriers to opportunity.

Senate Bill 3 – Supporting and Strengthening Families Act – sponsored by Senator Renee Unterman

This bill would allow parents experiencing “short-term difficulties that impair their ability to perform the regular and expected functions to provide care and support to their minor children” a way to confer the authority to act as a temporary guardian on behalf of their children without the trouble, time, and expense of a court proceeding. The intent behind this piece of legislation is to provide a “statutory mechanism” that helps preserve family stability.

This bill passed through the Senate 43-10 and is now in the hands of the House Judiciary Committee.

Legislative Calendar

Tomorrow (April 2, 2015) is Sine Die – the last day of the 2015 Legislative Session.

Reports

These are the house and senate reports on activity in each chamber.

– House Daily Report (daily)

– Senate Daily Report (weekly)

Use Our Website to Follow Important Legislation and Contact Your Elected Representatives

Visit our Take Action page to see all of the bills we’re tracking this session, to take specific actions on bills we support or oppose, and find out how to contact your elected representatives.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Mar 18, 2015

Critics of Educational Savings Accounts often raise the issue of the constitutional challenges of using taxpayer funds to purchase private education.

Recently, Jason Bedrick of the CATO Institute and Lindsey Burke of the Heritage Foundation highlighted this issue in their article published in National Affairs, writing, “While the United States Supreme Court has ruled that publicly funded school vouchers are constitutional under the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, most state constitutions contain a version of the so-called ‘Blaine Amendment,’ which bars state aid to parochial schools.”[1]

The Blaine Amendments owe their name to James G. Blaine, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, who proposed a U.S. constitutional amendment in 1875 prohibiting states from funding religious education. The amendment’s original intent was to prevent Catholics from acquiring taxpayer support for their schools. While his proposed amendment failed to become part of the U.S. Constitution, more than two-thirds of the 50 states adopted their own constitutional amendments barring state funding of religious organizations that include schools, which have come to be known as the Blaine Amendments.

To understand how the Blaine Amendments affect ESAs in Georgia, a recent report written by GCO Scholar Dr. Eric Wearne and the Georgia Public Policy Foundation provides important insight on this issue:[2]

In recent decades, these [Blaine] amendments have been interpreted by some to be prohibitions against any use of state funds for any schools other than public schools, and to prevent public funding of other faith-based initiatives, of any kind. Georgia’s Blaine Amendment reads:

…[n]o money shall ever be taken from the public treasury, directly or indirectly, in aid of any church, sect, cult, or religious denomination or of any sectarian institution. Ga. Const. art. I, § II, ¶ VII.

However, Title 20 of the Georgia Constitution also states that,

Educational assistance programs authorized. (a) Pursuant to laws now or hereafter enacted by the General Assembly, public funds may be expended for any of the following purposes:

(1) To provide grants, scholarships, loans, or other assistance to students and to parents of students for educational purposes.[3]

ESAs avoid many of the legal issues that may arise through other programs, such as vouchers and tuition tax credits… Matthew Ladner argues that “It is unlikely that ESAs would ever be less constitutionally robust than vouchers. … Designing programs so that the aid has multiple uses and is clearly under the complete control of parents can only help or be neutral in a constitutional challenge.”[4] Though vouchers have been held to be constitutional under certain conditions by the U.S. Supreme Court,[5] ESAs may avoid even these challenges.”[6]

Bedrick and Burke argue this point even further:

The example of Arizona is encouraging on this point for advocates of ESAs. Despite having previously struck down vouchers, in March 2014 the Arizona Supreme Court declined to review an appeals-court decision upholding the state’s ESA law. The court distinguished the ESAs from vouchers because the latter “set aside state money to allow students to attend private schools” whereas under the ESA law, “the state deposits funds into an account from which parents may draw to purchase a wide range of services” and “none of the ESA funds are pre-ordained for a particular destination.”

Given the precedent set by the Arizona Supreme Court and the authority granted by Title 20 of the Georgia Constitution, supporters of ESAs should not allow themselves to worry too much concerning the constitutionality of this innovative program.

Notes

[1] https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/the-next-step-in-school-choice

[2] https://georgiapolicy.org/ftp_files/ESA_121714.pdf

[3] https://sos.ga.gov/admin/files/Constitution_2013_Final_Printed.pdf

[4] https://www.edchoice.org/Research/Reports/The-Way-of-the-Future–Education-Savings-Accounts-for-Every-American-Family.aspx

[5] https://www.edreform.com/2012/01/legal-summary-zelman-v-simmons-harris/

[6] See, for example, the current challenge to Georgia’s Tax Credit program. https://reason.com/archives/2014/05/07/georgia-school-choice-legal-challenge

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 23, 2015

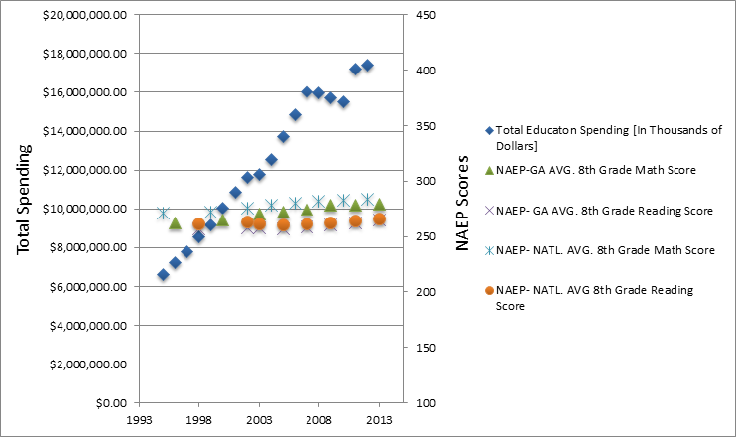

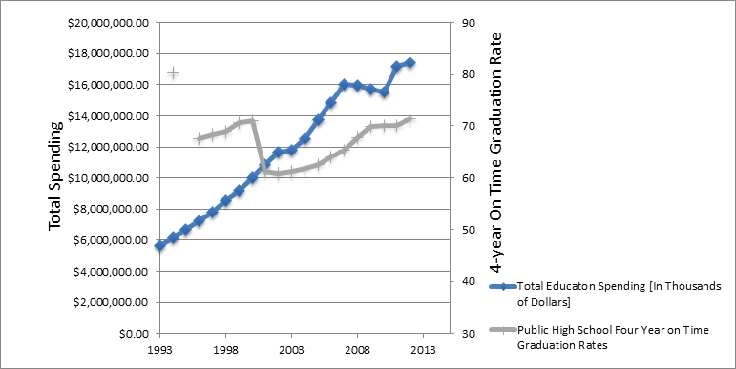

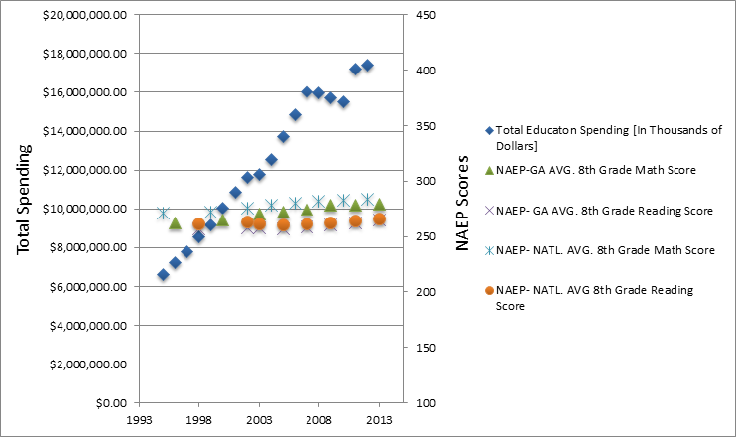

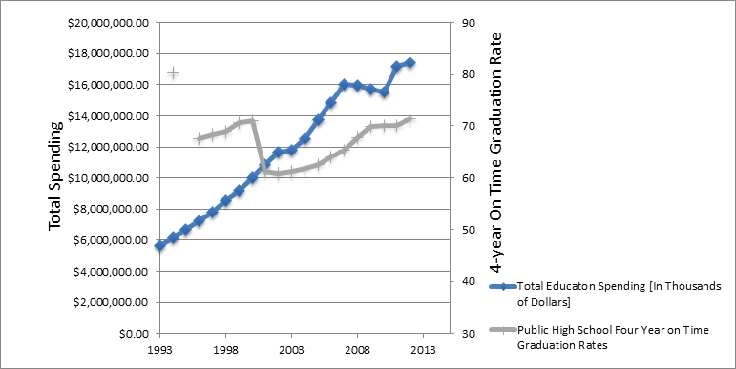

Attempts at reforming the public education system in Georgia are not new. Even just looking over the last 20 years, numerous reform efforts have been introduced as a means to improve educational outcomes among the state’s youth. Some of these ideas have had a better effect than others, yet as a whole they have not achieved the level of progress Georgia has hoped for. While modest gains have been made in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores for eighth grade students and the graduation rate for high school students has risen since 2002, Georgia still has a grade of C-Minus overall and one of the lowest graduation rates in the country.

Below is a list of reforms that Georgia has tried since the introduction of the Hope Scholarship and the charter school law that was passed in 1993. Comparing these reforms to the two graphs that follow demonstrates that achievement among Georgia’s eighth grade and high school students has been relatively stagnant compared to the amount of money spent to improve education over the last two decades.

Past Reforms

1993 – HOPE Scholarship created and funded by lottery. Charter school law passed; only public schools can convert to charters; commissioned by local and state board.

2000 – A+ Education Act mandates end-of-course assessments and Criterion-Referenced Competency Test (CRCT) in core subjects.

2001 – No Child Left Behind and Title I grants public schools with high percentages of students receiving free or reduced lunch additional federal funding.

2005 – Georgia Performance Standards implemented as a result of Quality Core Curriculum (QCC) reform to align with national standards.

2008 – HB 881 creates the Georgia Charter Schools Commission. Qualified Education Expense (QEE) Tax Credit Bill passed (HB 1183).

2009 – American Recovery Reinvestment Act; Georgia received almost $2 billion dollars to invest in education. HB555 requires local schools systems to grant charters within the district access to unoccupied buildings at no cost.

2010 – As a result of Common Core State Standards initiative, Georgia adopts new content standards in language arts, math, science, and social studies.

2011 – HB881 Georgia Charter Commission declared unconstitutional; 16 charters, 15,000 students impacted. QEE Tax Credit Bill amended (HB 325) creating student scholarship organizations (SSOs); individual and corporate taxpayers can contribute to SSOs in exchange for a state tax credit.

2012 – Amendment One passes and Georgia Charter Commission is reinstated. College and Career Performance Readiness Index (CCPRI) conducted “study year” of public schools’ performance.

2013 – Tax Credit Bill amended (HB283); cap increased to $58 million. Career Clusters curriculum implemented in schools.

2014 – Students are to take Georgia Milestones instead of CRCT and EOCT. Charter schools reach a total of 315.

- 77 start-ups

- 31 conversions

- 207 charter system schools

- 16 charter systems

- 13 state commissioned specialty schools

- 13.5% of total student population

Total Spending vs. NAEP Scores

Total Spending vs. High School Graduation Rate

It seems that Georgia will have to do something different than what has been attempted thus far if we want to experience real gains in educational outcomes among K-12 students – something different than pumping more money into the current system, aligning state curriculum to national standards, or allowing only a limited number of parents and students school choice. We need greater options that ensure tax dollars are well spent and students’ educational needs are met. Only then will be begin to see a more dramatic increase in the number of high school graduates who are ready for college, career, and life.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 11, 2015

Georgia’s public school system is failing many of our children, and it seems everybody has an opinion in regard to what needs to happen. But one truism has become apparent: More money is not the solution.

Nationally, spending on public education in constant dollars has nearly tripled since 1970, and the expenditures per student have doubled from $4,500 per student per year in 1970 to almost $11,000 today.[1] During this same time period, the National Average for Educational Progress (NAEP) scores for 17-year-olds have remained essentially unchanged. Americans spend more money per-student than any other nation in the world while only performing in the middle-to-back of the pack among developed countries.

While an increase in spending has not yielded higher achievement scores among U.S. students, it has been successful in accomplishing one thing: increasing the size of school administration. Since 1950, the overall number of school administrators in the U.S. has risen by a staggering 702 percent, while the number of teachers has only grown by 252 percent, and the number of students has increased by only 96 percent.[2] For all this growth in school administration and faculty, the outcomes in student achievement have been disappointing.

The same can be said for Georgia. Spending on public education increased drastically from $5.6 billion in 1993 to $17.4 billion in 2012, yielding an improved student-teacher ratio during this time period (16.7 in 1993 to 15.6 in 2012). Yet despite all this spending and having more teachers and smaller classroom sizes, NAEP scores for eighth grade students in Georgia remained virtually the same. Similarly, the high school graduation rate did not improve significantly during this time period, going from 67.6 percent in 1996 to 71.5 percent in 2012, while hitting a low of 60.8 percent in 2002.

Both in Georgia and nationally we continue to operate under the assumption that more money and more staff will solve the problem of a failing educational system. However, statistic after statistic indicates that pouring more money into Georgia’s failing public school system will not provide any substantial improvement, especially for Georgia’s most vulnerable children. There have, and continue to be, serious and well-intentioned efforts to reform the system. But because these reforms only provide minor changes to the system without seeking to change the way the system is organized, they limit themselves to minor improvements in standardized test scores.

In order to improve the educational opportunities we give Georgia’s children and ensure that the money spent on public education is not wasted on poor results, Georgia needs a new and innovative approach to education – an approach that gives parents the power to see their children succeed in education and in life. We need quality instruction that meets the needs of an enormously diverse group of students in a broad range of circumstances.

This just might be the power that newly proposed Education Savings Accounts offer.

Notes

[1] McShane, Michael. How America’s Education System Fails to Live Up to Its Promises (Washington, DC: AEI Press, 2015).

[2] Ibid.

by Georgia Center for Opportunity | Feb 6, 2015

According to the most recent data released by the National Center for Education Statistics this January, Georgia’s high school graduation rate is still one of the lowest in the nation at 72 percent, despite good improvement over the last two years. Only three states and the District of Columbia have a lower graduation rate than Georgia. Compare this to such states as Nebraska, New Jersey, North Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin, which all have a graduation rate of 88, and Iowa which leads the pack at 90.

Georgia’s struggles don’t end with its graduation rate. Education Week released the latest report cards for each state this January in the categories of Chance-for-Success, School Finance, and K-12 Achievement in its 19th annual Quality Counts – Preparing to Launch: Early Childhood’s Academic Countdown. Georgia earned a grade of C-Minus and a ranking of 31st overall amongst the 50 states, based on its rankings of 37th, 31st, and 17th in each respective category. Georgia is below the nation as a whole, which earned a grade of C.

It would be one thing if Georgia ranked near the middle of the pack in a country whose educational outcomes far exceeded those of other developing countries around the world. However, when comparing how the U.S. education system stacks up on the international playing field, the results are not promising.

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessed the competencies of 15-year-olds in reading, mathematics, and science in 65 countries and economies in 2012. Among the 34 countries who are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the U.S. performed below average in mathematics, ranking 27th, and close to the OECD average in reading and science, ranking 17th and 20th respectively. According to PISA, U.S. students’ performance has not changed significantly over time despite the U.S. spending more per student than most countries.

So, what do these statistics teach us?

If Georgia stands in the middle of the pack when compared to other states in educating our children, in a country that is in the middle-to-the-back of the pack among developed countries, it’s safe to conclude that as a state we are failing to produce the level of excellence we desire for our children in an increasingly globalized economy.

Far too many students are stuck in failing schools that stifle them from reaching their full potential simply because their zip code affords them no other options. As a state, we cannot afford to let students spend another day in a failing school. The cost is too high individually and collectively.

Mediocre results call for a change in the status quo. Instead of keeping the same old system that is failing to produce the outcomes we hope to see, why not try a different strategy?