Safety Net Solutions for North Carolina

Contents:

Who Are We

Center for the Study of Economic Mobility

Craig Richardson has served as founding director since 2018 and is the Truist Distinguished Professor of Economics at Winston-Salem State University. CSEM’s primary focus is on researching the causes and solutions for low economic mobility, using his resident Forsyth County as a proving ground. Since 2018, CSEM’s work on public transportation, benefits cliffs and the housing market has led to a host of well-cited research publications, op-eds in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The American Institute of Economic Research as well as many other media outlets. CSEM has also distributed three educational documentaries that have circulated nationally on innovation in public transportation and affordable housing.

More information on Craig Richardson’s writing here.

How we unintentionally created the affordable housing crisis. by Yuliya Panfil and Craig Richardson. The New York Times op-ed. Oct. 3, 2024.

Welfare Benefits and the ‘Disincentive Desert- How Americans became ensnared in the system. The Wall Street Journal. (letter to editor). by Craig Richardson. Dec. 11, 2023.

Why disincentive deserts matter more than benefits cliffs. By Craig Richardson. American Institute for Economic Research. Feb. 13, 2023.

“Benefits cliffs, disincentive deserts, and economic mobility”

by Craig Richardson and Zachary Blizard. Journal of Poverty, 26 (21), pp. 1-21. 2022

Georgia Center for Opportunity

Erik Randolph is the director of research for the Georgia Center for Opportunity, a 501(c) nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to advance opportunities proven to be escape routes from poverty. A major activity of the Center is finding solutions to safety-net benefit cliffs and other obstacles that hold people back. The Center has built the most robust computer model of safety-net eligibility systems that includes every county in the state of North Carolina. Activities of the Center extend far beyond the borders of Georgia to working with 17 states and the District of Columbia to one degree or another plus actively working on ways the federal government can improve safety-net programs.

More on GCO studies on benefit cliffs relating to North Carolina.

Solving Medical Assistance Benefits: Removing the Healthcare Barriers that Trap People in Poverty, by Erik Randolph, Revised April 17, 2025,: https://foropportunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Solving-Medical-Assistance-Benefits-GCO-2025Ap17.pdf

The NC Benefits Cliffs Program—And It’s Worse Than You Think: The Limited Prospects for a Single Mom in North Carolina, the Cliffs Explained, and Some Actionable Ways to Find Solutions, by Erik Randolph, March 20, 2024:

- Research Briefing https://d1f2pmkajn85sd.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Research-Brief-No-2024-02-North-Carolina-Cliffs.pdf

- Full Report: https://d1f2pmkajn85sd.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/The-NC-Benefits-Problem.pdf

Solving the Food Assistance (SNAP) Benefits Cliffs, by Erik Randolph, October 3, 2023: https://foropportunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/SNAP-Cliffs-Solution-v1.9.pdf.

Op-eds in the Carolina Journal

“Medicaid expanded NC health-care access. But this fix could make it run smoother.” by Craig J. Richardson and Erik Randolph, April 16, 2025:https://www.carolinajournal.com/opinion/medicaid-expanded-nc-health-care-access-but-a-fix-could-make-it-run-smoother/

“What if Medicaid Were Run More Like Target?” by Craig J. Richardson and Erik Randolph, April 23, 2025: [Add Link When Available]

“Should the Market for Health Insurance Be More Like Car Insurance? The Ultimate Solution to Fix More than Just Medicaid” by Craig J. Richardson and Erik Randolph, April 30, 2025: [Add Link When Available]

Medical Assistance Program

Medicaid and CHIP

What are they?

Enacted in 1965, Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that originally covered individuals with disabilities and families of low means with dependent children. But Medicaid has been expanded numerous times to cover more of the population, including the most recent expansion allowing states to cover all adults up to 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) pursuant to the Affordable Care Act (2010). The 138 percent includes a mandated 5% income disregard. The most recent Medicaid expansion is optional for the states, and North Carolina expanded its coverage on December 1, 2023.

The Children’s Health Insurance Program is another joint federal-state program enacted in 1997. CHIP provides coverage for children under 19 whose families fall within their state’s FPL limit, which varies by the child’s age and who do not qualify for Medicaid. On April 1, 2023, North Carolina ended its separate CHIP program and merged it into Medicaid.

Who is covered?

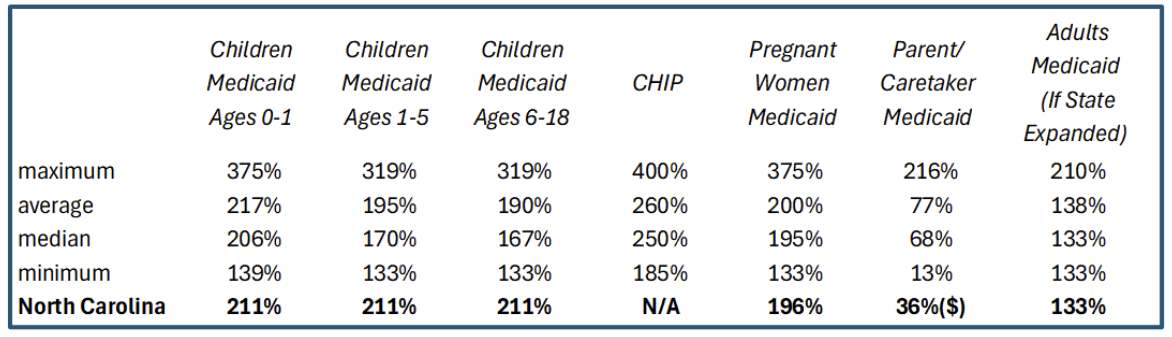

Table 1 summarizes the basic income eligibility limits for both Medicaid and CHIP as a percent of Federal Poverty Level (FPL) as of April 2025. The table shows the limit ranges by category for all states and the District of Columbia. It shows the statutory FPLs and does not include the 5% income disregard for the expansion adults. The ($) symbol next to North Carolina’s 36% for Parent/Caretaker Medicaid means that North Carolina uses a flat dollar amount, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that oversees the Medicaid program converted the amount to be approximately 36% of FPL. Because North Carolina expanded, the Medicaid amount income limit for parent or caretaker is obsolete as the state is using the limit for the expansion adults.

State Variance of Medicaid and CHIP Income Eligibility Limits as a Percent of FPL

For Medicaid, federal law allows for cost sharing above 100 percent of FPL, but at or below 150 percent of FPL, the cost sharing cannot include premium shares. CHIP allows states to charge premiums or enrollment fees, but only 18 states do.

Health Insurance Exchanges (HIX) Subsidies

What are HIX subsidies?

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 created government-run Health Insurance Exchanges (HIX) for individual markets, which also are referred to as the Marketplace. Each state was divided into regional rating areas, and consumers shop within those rating areas. The ACA attempted to achieve universal coverage by relying on a hodge-podge of health insurance programs, including large-employer-sponsored insurance for employees, Medicaid, CHIP, Medicare, TriNet, HIX, and small-business marketplaces. Specifically, ACA:

- mandated employers with 50 or more employees to provide health insurance with adequate benefits for their employees

- required states to expand Medicaid to cover adults up to 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level, which was later overturned by a 7-to-2 U.S. Supreme Court decision making the expansion voluntary for the states

- established HIX for those with incomes at or above the Federal Poverty Level, and

- created the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) for small businesses with less than 50 employees to purchase health insurance for their employees. SHOP essentially failed as a program, and it was phased out and is no longer available.

However, purchasing insurance through HIX is still available for individuals and families. The primary subsidy for HIX is the premium tax credit that underwrites the cost for consumers. During the year, the subsidies go directly to the insurance companies selected by the consumer, known as advance premium tax credits. Consumers are required to reconcile the subsidy at the end of the tax year with their federal tax filings. They may receive a Premium Tax Credit refund if the monthly advance premium tax credits were too little, or they may owe the difference if the monthly advance premium tax credits were higher than what the consumer was eligible to receive.

In addition to the premium tax credit, there are mandates on insurers that benefit purchasers with incomes over 100 percent but under 250 percent of FPL by shifting those costs to others.

42 U.S. Code 1396o

Tricia Brooks, Jennifer Tolbert, Anna Mudumala, Amaya Diana, Allexa Gardner, Aubrianna Osorio, and Shoshi, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Renewal Policies as States Resume Routine Operations Following the Unwinding of the Pandemic-Era Continuous Enrollment Provision, KFF, April 1, 2025, Table 28: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-renewal-policies-as-states-resume-routine-operations-report. In 2020, 30 states charged premiums or enrollment fees: Tricia Brooks, Lauren Roygardner, Samantha Artiga, Oliva Pham, and Rachel Dolan, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2020: Findings from a 50-State Survey, KFF, March 2020, Table 14: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Medicaid-and-CHIP-Eligibility,-Enrollment-and-Cost-Sharing-Policies-as-of-January-2020.pdf

Who is eligible?

The Affordable Care Act created a tiered system of Platinum, Gold, Silver, Bronze, and Catastrophic plans, which are in descending order of how much of health care costs they cover with Platinum covering the most and Catastrophic covering the least with the latter also having limiting criteria for participation. The act also created regional HIX rating areas throughout the country, and the details of each insurer’s plan and its costs are specific to each rating area. The Second Lowest Cost Silver Plan of each rating area forms the basis for the Premium Tax Credit. A sliding scale was established by the Act and determines the amount of premium share of the SLCSP the tax filer must pay, which increases as a percent of the tax filer’s modified adjusted gross income based on the prior year’s FPL, up to a maximum of 8.5 percent for Tax Years 2021 through 2025, but otherwise a maximum of 9.5 percent. The difference between the cost of the SLCSP and the tax filer’s calculated premium share of the SLCSP is the amount of the subsidy, provided the subsidy does not exceed the cost of the SLCSP.

Problems with the Current System

Affordability and Cliffs

When do medical assistance benefit cliffs occur?

Benefit cliffs occur when adults lose Medicaid or children lose CHIP due to increased income above eligibility limits, leading to transitions into private insurance, HIX plans, or, in some cases, no coverage at all.

How does it happen?

Coming off Medicaid and CHIP onto employer-sponsored plans can have a benefits loss because of premium shares, deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments. In 2024, for example, 19 percent of employees were ineligible for their employer’s health benefits. Twenty-five percent of those eligible did not take up the benefits offered to them, and workers who did take up their employer’s plan paid on average 16 percent of the cost of the premium for single coverage plan, or $1,368 annually, and 25 percent for family coverage, or $6,296 annually. These are unaccustomed costs that would be imposed on those who previously had Medicaid.

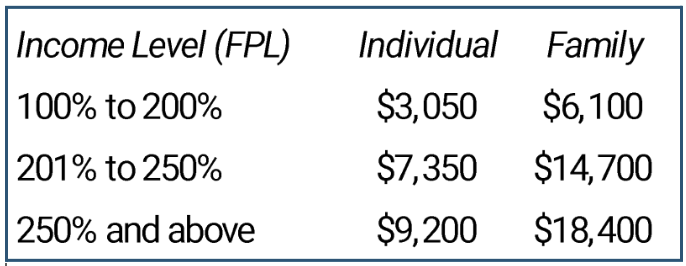

If the plans offered by an employer are deemed inadequate or unaffordable, or if the family or individual is not offered an employer’s plan, they may access coverage through HIX. However, the out-of-pocket costs may still be perceived as and can indeed be unaffordable despite the subsidies to lower out-of-pocket costs. Consistent with Medicaid rules, premium shares ease in on a sliding scale starting at 150 percent of FPL. Table 2 provides the HIX out-of-pocket cost limits for 2025.

Public Law 117—2, March 11, 2021, and Public Law 117—169, August 16, 2022

Gary Claxton, Matthew Rae, Aubrey Winger, and Emma Wager, Employer Health Benefits: 2024 Annual Survey, KFF, pp. 64, 68, and 83: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Employer-Health-Benefits-Survey-2024-Annual-Survey.pdf.

Annual Cost Sharing HIX Plans for 2025

What System People Deserve and Obstacles

What characteristics of a health care system serve people best?

If we would list the characteristics of a health care system, what would they be? The Georgia Center for Opportunity did just that in two different papers. The following list summarizes what those characteristics would be.

- Freedom to choose insurers and providers of their care. This creates more options for consumers giving them more control over their insurance plans and healthcare.

- Ability to shop for health insurance with real choices among many insurers. Competition among many insurance companies makes for better choices for consumers and helps drive down prices.

- The right coverage when needing medical care. It is important that coverage is there when needed.

- Coverage for routine screening and preventative care. Health policies that encourage screening and preventative care help lower insurance costs by catching conditions earlier when they are more treatable and less costly. This is also good for consumers.

For an explanation of subsidies to lower out-of-pocket costs, see Louise Norris, “The ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies,” healthinsurance.org webpage, posted January 15,2024: https://www.healthinsurance.org/obamacare/the-acas-cost-sharing-subsidies.

Table 2 data from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, Memorandum, “Premium Adjustment Percentage, Maximum Annual Limitation on Cost Sharing, Reduced Maximum Annual Limitation on Cost Sharing, and Required Contribution Percentage for the 2025 Benefit Year ,” December 15, 2023: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2025-papi-parameters-guidance-2023-11-15.pdf.

Erik Randolph, A Real Solution for Health Insurance and Medical Assistance, Georgia Center for Opportunity, January 2018: https://georgiaopportunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/WEB-A-Real-Solution-for-Health-Insurance-.pdf and Erik Randolph, What Does An Ideal Solution To The Health Insurance Crisis Look Like? Principles for Policymakers when Crafting a Federal Waiver Application. Georgia Center for Opportunity, July 2019: https://foropportunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/19-057-GCO-HealthCare-Ideal2.pdf.

- Quality care. Consumers like to be treated like human beings getting quality care from health professionals where they don’t feel like they are being treated like a number. Here, health outcomes are important. Some studies have shown that some programs, like Medicaid, have bad health outcomes when compared to other types of health care coverage.

- Innovation that improves medical care or makes it more affordable. Not all health systems encourage innovation. Bureaucratic systems, such as nationalized health care or monopoly-owned systems, are notorious for lacking innovation. Competition among providers is known best for driving innovation

- Access to the most appropriate and advanced treatments. As a byproduct of innovation, Americans expect and even take for granted advancements in medical care. The overall system must continue to do the same. America has been leading the world in advancing medical advancements, and it would be a disservice if any system change would hinder the trend. In addition, consumers want access to those advanced treatments when they need them. Not all Americans have access, depending on their health policies, such as Medicaid or some employer-sponsored policies that limit coverage to provider networks and predetermined treatments.

- Portability of plans. Consumers like to be able to take their health plans with them whenever they lose or change jobs.

- Continuance of a plan when becoming sick and unable to work. Nothing is more frustrating than if a person loses healthcare coverage when becoming sick and needing it. Therefore, it is important that they have some guarantee that they can keep their policy when they become sick.

What are the barriers to a well-functioning health care system?

It is well-known among economists that health insurance markets do not function like other markets. Health insurance faces identifiable obstacles not found in other industries.If these obstacles can be addressed, then health insurance can be made to function like any other successful market structure. The obstacles are as follows.

- Pre-existing conditions that prevent attaining affordable insurance. Perhaps the greatest barrier to a well-functioning health insurance market is pre-existing conditions. Once someone has a pre-existing condition, it raises the cost of care that negatively affects the profitability of the insurance company that must carefully monitor costs so as not to become insolvent.

- Lack of universal coverage where not all citizens have health coverage. The current design of the American health insurance industry still lacks universal coverage. If the barriers of pre-existing conditions can be solved along with a system of subsidizing those cannot afford health insurance, then universal coverage can be achieved.

- Third-party payor system that separates consumer behavior from costs. A major obstacle with the American health insurance system is that it is funded by a third-party payor. The person paying the cost of insurance is mostly the employer or the government, which separates the consumer from normal price signals of supply and demand. This can cause an overconsumption of health care. Worse, because the payor is not the person receiving the care, they are separated from the benefits received, possibly making them not care as much.

- Opaque pricing that hides the cost of medical services beforehand. A major barrier is that it is very difficult to know ahead of time what a particular medical service will cost. Medical providers and insurance companies negotiate prices of services to such a degree that different policyholders are paying different prices for the same services. Government programs like Medicare and Medicaid make the situation worse by dictating prices that do not always reflect the real cost.

- Cream skimming where insurers prioritize healthy individuals for coverage. In order to avoid customers with high healthcare costs, some insurance companies have been prioritizing healthier individuals enabling them to charge lower costs. While this may be good for that company and its customers, it pushes the costs of more costly customers onto other insurance companies or government programs.

- Adverse selection that raises costs for insurers, distorting the market. The opposite problem of cream skimming is adverse selection. Those having higher costs tend to be more aggressive in seeking out health insurance while those with little to no costs may decide to sit out without any coverage at all, at least when they are young and healthy. This phenomenon raises the cost of insurance.

- Lack of portability where losing a job means losing health coverage. Not being able to take your health insurance with you, even if you like your health insurance, can be disruptive when someone loses their employment. It can also dampen job flows for those who want to switch jobs or start their own business when they realize they will lose health insurance. Federal law addresses portability with a provision in the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, often referred to by its acronym COBRA. Enacted in 1986, COBRA does allow those who lose employment to keep their policy for a limited time but for the full cost plus an administrative fee. For most workers, the time limit is 18 months.

Solutions

Improving Medicaid

Can Medicaid Be Run More Like Target, Inc.?

North Carolina can improve its Medicaid program that gives recipients more control of their healthcare spending and offers a bridge program that will ease the transition off Medicaid. While this is not a complete solution to healthcare coverage, it does make major strides in improving the current program and would be easier to undertake than the more complete solution.

Public Law 99-272, April 7, 1986, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985, and U.S. Department of Labor Employee Benefits Security Administration, FAQs on COBRA Continuation Health Coveragefor Employers and Advisers, December 2018: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs/cobra-continuation-health-coverage.pdf.

The fundamental question is this: Can North Carolina change its Medicaid program to run like an innovative, customer-friendly corporation such as Target, Inc.? Is this at all possible? Learn more about Indiana’s Medicaid program that does that here.

Indiana’s Medicaid program may be doing just that, using some novel practices that gives recipients more control and vastly improves how people transition from Medicaid to private sector health insurance. What’s more, it delivers better health care outcomes at a lower cost, with some important takeaway lessons for the state of North Carolina.

Let’s put the federal Medicaid program into perspective first.

Medicaid spent $872 billion in 2023 and is one of our largest federal government programs, with expenditures about eight and half times the size of Target’s annual sales, at $103 billion that same year.

Medicaid’s reach is far and wide: it includes $1 out of every $5 spent on health care in the U.S. and provides health coverage and long-term care for low-income residents.

It directs ponderous federal rules that dictate how the healthcare is delivered, and how much federal funding each state gets to run its own Medicaid program, ranging from a 50% subsidy (New York) to a 77% subsidy (Mississippi). States follow regulations that come from Washington and have limited power to change them.

What makes a company like Target different?

Target, on the other hand, is a successful multinational corporation with company-wide strategic goals. Competing with other companies, it customizes its product selections based on local customer needs and economic conditions, or it risks losing money. Adaptation and experimentation, unusual words for government programs, is the name of the game for a successful company like Target.

So what’s the problem right now with Medicaid?

When North Carolina helped 600,000 newly eligible families get health care through an expansion in the Medicaid program, it solved one problem but not others.

One, NC Medicaid is still an expensive proposition, costing $20.5 billion in state and federal taxpayer funds in 2023, or just over $7,000 per Medicaid recipient.

Two, transitioning from Medicaid to a privately run or government subsidized health insurance program can be highly stressful, for reasons we discussed in a previous article.

How can innovation help make Medicaid better?

But private sector-like innovation in health care delivery is possible while delivering improved health and economic mobility outcomes and keeping state budgets neutral. It’s known as the “Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver” and allows states to act more like a Target.

Section 1115 waivers are a way for states to experiment in different ways that may be better than the top-down approach favored by the federally mandated Medicaid program. Waivers have been used to expand coverage or benefits, change policies for existing Medicaid populations, modify how healthcare is delivered (say through Zoom interviews vs in-office visits), or change incentives for how patients receive health care.

Innovation in Indiana: How does it improve the transition from Medicaid to the private sector?

The “Healthy Indiana Plan” (HIP), begun in 2008, provides an example for North Carolina, with innovative approaches to improving health outcomes as well as the transition from Medicaid to the private sector.

HIP has been successful in lowering uninsured rates and improving the health of its Medicaid participants with one simple idea. It puts more power in the hands of individuals to make personal health care decisions, just like giving choosy Target shoppers a gift card they can use now or in the near future. Here is a

What are the specifics of the Indiana Plan?

Specifically, each Medicaid recipient on the Indiana HIP plan receives a $2,500 “Personal Wellness and Responsibility” (POWER) debit card to use for the year’s health expenses, which pays for the first $2,500 in medical services in a given year. HIP members contribute a modest monthly amount between $1 to $20 for the POWER account, and employers can also contribute up to 50% of the monthly cost. In addition, the state gives free preventive health care and $20 gift cards for each visit.

If annual health expenses rise above $2,500 and HIP members have been making consistent monthly payments, the additional health services are fully covered at no cost. What’s more, the POWER account gets refilled again at the beginning of the next calendar year with another $2,500. If the members still have money left at the end of the year, those remaining funds can be used to lower next year’s monthly payments.

The advantage of this program is that Indiana citizens have some power and control over their health, thinking wisely about those decisions in the same way as we manage a Target gift card, to use some today (or not) and saving funds for a future time. The HIP program incentivizes people to get preventive health care, eat well and exercise, rather than having a bottomless bowl of reimbursements that don’t recognize people’s improving health habits.

Image of POWER Card

After using their POWER card for a medical expense, users get a receipt that shows the cost of each health care service as well as the amount left in their POWER account, giving them a way to track health care spending just as we do in other areas of our lives. Here is a short video explaining how it works: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b4vNxdcCPaY

The Indiana program works with private Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to facilitate Medicaid coverage. These MCOs earn a flat fee for Medicaid enrollees and thus gain higher profits as people’s health improves, with the aim of aligning their incentives with the state residents.

What happened after Indiana introduced their new system?

In 2018 the state saw a dramatic increase in preventive services, mammograms and vaccinations as well as smoking cessation therapies. Pregnancy management programs skyrocketed by an annual 41 percent from 2015 to 2018. By 2016, ER usage compared to traditional Medicaid programs had fallen by 30 percent as individuals sought local clinics for non-emergency ailments.

Indiana has also figured out how to improve the transition after a rise in salary leads to a sudden drop-off in Medicaid eligibility. Residents get to use $1,000 from their POWER medical savings accounts for up to 12 months to pay premiums, deductibles, copays and coinsurance during their transition to commercial coverage. It’s called the “Workforce Bridge Program” and Indiana was the first state to establish this innovative approach.

A Medicaid bridge program, such as one adopted by the state of Indiana with a Section 1115 waiver approved by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), can ease the situation for individuals exiting Medicaid.

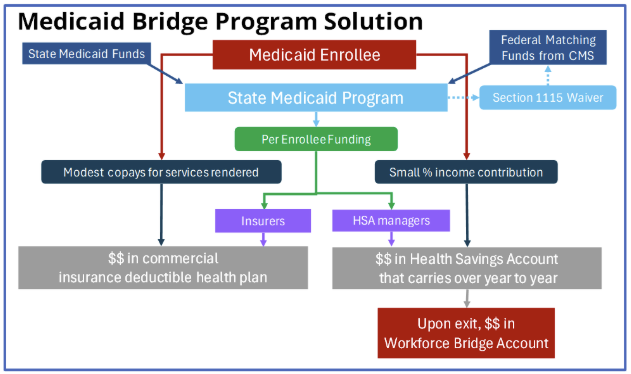

How North Carolina Can Improve Medicaid

North Carolina can adopt its own Medicaid Healthy Plan using an approved Section 1115 waiver. The plan would split Medicaid benefits into two parts. The first part is a standard commercial insurance plan with deductibles. The second part is a health savings account (HSA) that allows enrollees to carry over funds year to year. Program participants contribute a small percentage of their income to the health savings account and may use the funds in their accounts to pay out-of-pocket health-related expenses, including deductibles and copays, that are not covered by the deductible plan.

When exiting Medicaid, North Carolina can allow participants to keep a portion of their Health Savings Account in a new account called a Workforce Bridge Account, which was approved for Indiana by CMS in 2020. The intention is to help the person with higher out-of-pocket expenses during the transition until the person can become more financially established. Figure 1 provides a schematic of how the bridge program would work.

Figure 1

Comprehensive and Permanent Solution

The big picture

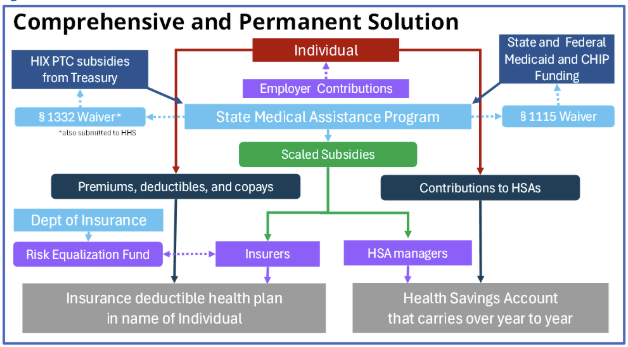

Despite being a partial solution, a bridge program like Indiana’s can be used as a building block for states to adopt a comprehensive and permanent solution. A consumer-driven, market-based risk equalization system relying on American entrepreneurship and innovation solves the most vexing problems of pre-existing conditions, universal coverage, third-payor system, cream skimming, adverse selection, and portability while preserving quality of care for a health system that provides the most advanced treatments.

A consumer-driven, market-based risk equalization system approaches the problem from an actuarial basis, and a state could easily adopt the principles to its circumstances. The mechanics are all behind the scenes, out of view of consumers, giving them a seamless experience.

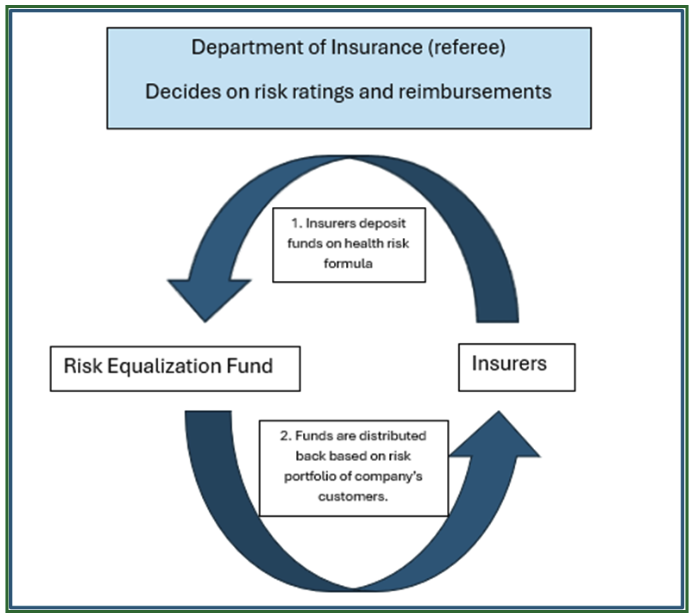

As the name suggests, central to this solution is a risk equalization fund among insurers. Each insurer puts money into the fund, and money is returned to insurers based on a risk-assessment formula. No taxpayer money goes into the fund, and the fund works on a zero-sum basis, meaning the money coming into the fund from the insurance companies will go back to the insurer companies based on a formula that is fair and equalizes risk. The formula uses true actuarial costs calculated regionally, independent of any insurer’s portfolio, to assess risk differences, with insurers managing higher-risk portfolios receiving more from the fund than those with lower risk portfolios. An impartial overseer, such as a state’s insurance department that already regulates insurance companies, acts as a referee. The basic idea is equalizing risks without rewarding inefficient insurers. Figure 2 shows how the risk equalization fund works.

Figure 2

See Regina E. Herzlinger, ed., Consumer-Driven Health Care: Implications for Providers, Payers, and Policymakers, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Imprint, 2004, and Regina Herzlinger, Who Killed Health Care? McGraw-Hill, 2007. The idea of consumer-driven, market-based risk equalization was pioneered in Switzerland and successfully adapted by the Netherlands. See also various writings of Avik Roy, including his The Apothecary blog, such as Avik Roy, “Why Switzerland Has the World’s Best Health Care System,” Forbes, April 28, 2011, and Avik Roy, “Switzerland: A Case Study in Consumer-Driven Health Care,” Forbes, December 26, 2012. See also Robert E. Leu, Frans F. H. Rutten, Werner Brouwer, Pius Matter, and Christian Rütschi, The Swiss and Dutch Health Insurance Systems: Universal Coverage and Regulated Competitive Insurance Markets, Pub. No. 1220, Commonwealth Fund, January 2009: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2009/jan/swiss-and-dutch-health-insurance-systems-universal-coverage-and.

Figure 3 gives a schematic of how a comprehensive and permanent solution would work. Note the similarities to the Medicaid Bridge Program. The new solution also depends on normal private-sector health insurance policies and health savings accounts, just like with the Healthy Indiana Plan. But now we’re extending the solution to everyone not on Medicare and we added the all-important risk equalization fund as a component. Instead of splitting government subsidies into different pots of money, we are consolidating them into a single subsidy program that will be run by the state of North Carolina. Section 1332 of the Affordable Care Act allows states to access these funds for health coverage reform using a demonstration waiver. Section 1332 waivers are a powerful tool available to the states to adopt more meaningful, comprehensive, and permanent solutions.

Figure 3

The current premium tax credit and the HIX rating areas will work well with the proposed comprehensive solution, and states can create such a system using a Section 1332 waiver of the Affordable Care Act in addition to a Section 1115 waiver. States will be able to combine the HIX subsidies, including funds for the premium tax credit, with Medicaid and CHIP funds to use as sliding-scale subsidies to enable everyone to afford health insurance and health savings accounts.

An important requirement for the system to work is that policies must be written in the name of individuals. Employers may still pay for the policies, but the employees would own them, allowing them to keep their insurance if they lose or change employment.

Why risk equalization works

This proposed solution relies on proven practice and on how insurance works. Risk equalization systems are already being used by the Netherlands and Switzerland with great success. Therefore, the proposal is not theoretical but based on practice.

At a basic level, an insurer’s revenue, which is primarily driven by premiums, must exceed the payouts for claims, otherwise the company risks insolvency. Because this proposed solution addresses the issue from an actuarial basis, it protects the solvency of insurers while maximizing benefits to consumers. Insolvency helps no one, especially insured individuals depending on the protection that the insurance provides. In contrast, the status quo system is showing stress as insurers are forced to adopt tactics that undermine the basic characteristics of a system that people deserve, which was outlined in a prior section of this briefing.

For example, suppose a fire insurer could somehow know in advance which customers would not have fires and selects only those customers. This would enable the company to offer below market rates, leaving higher cost individuals to be picked up by other insurers, causing their competitors’ rates to be higher. Cream skimming is a common issue in the health insurance industry, where insurers assess potential clients to estimate costs to their portfolio, avoiding high-risk customers or charging them significantly higher premiums—a practice not strictly cream skimming but a natural outcome of how health insurance has developed in America.

It is important not to confuse risk equalization systems with high risk pools, which are one way states have tried to address the negative consequences of unaffordable health insurance for high risk customers. In a high risk pool, insurance is offered to those with medical conditions that make obtaining insurance on their own unaffordable. This approach relies heavily on subsidies from the government and places individuals with serious health conditions in a stressful and untenable position until they get enrolled in the program. Additionally, there are always those who miss the eligibility cutoff and continue to suffer with exorbitantly priced or unaffordable health insurance.

Reinsurance is a common industry tool to distribute an insurer’s risk, protecting them against a surge in claims or a single large claim that exceeds their financial capacity. Reinsurance can be thought of as insurance for insurance companies.

Risk Equalization Systems work similarly to the way reinsurance works, but the mechanics are different. An actuarial basis is calculated for an entire demographic group within a geographical area, which serves as a guide for evaluating the risk characteristics of each insurer. All insurers put money into a fund, and then those with higher risk portfolios receive money from the fund to compensate them for serving higher risk customers. This equalization levels the playing field, solving the problems of cream skimming, pre-existing conditions, and the unwillingness of insurers to take on higher cost individuals.

This approach promotes fair competition with pricing based on true actuarial costs while leveraging all the advantages of private insurance. When coupled with a subsidy system to assist low-income families in purchasing insurance, it solves the issues of portability and universal coverage. When universal coverage is achieved, so is the problem of adverse selection solved. Finally, it avoids the severe pitfalls of nationalized health systems, such as Great Britain’s National Health Service or the Canadian Health Care System, that are bureaucratic, stifle innovation, sacrifice quality of care, and have long waiting lists to get care, which explains why wealthy individuals from those countries avoid their own healthcare systems and travel to the United States for meeting their healthcare needs.

John C. Goodman, Gerald L. Musgrave, and Devon M. Herrick, with a foreword by Milton Friedman, Lives at Risk: Single-Payer National Health Insurance around the World, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, published in cooperation with the National Center for Policy Analysis, 2004, especially pp. 38, 69, 131, 132. For wealthy consumers traveling to the U.S. for their care, see Tricia J. Johnson and Andrew N. Garman. “Demand for international medical travel to the USA.” Tourism Economics, Vol. 21, No. 5, October 2015, pp 1061-1077: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.5367/te.2014.0393; Randi Druzin, “Crossing the Border for Care,” U.S. News, August 3, 2016: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2016-08-03/canadians-increasingly-come-to-us-for-health-care; Danny Buckland, “200,000 Desperate Britons Go Abroad for Medical Care as NHS Waiting Lists Spiral,” Express, April 14, 2015, updated April 24, 2015: http://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/570305/Britons-NHS-waiting-lists-medical-treatment.